Well Preserved: Bear Creek Dam and Bear Creek watershed

Published 7:00 pm Thursday, December 1, 2016

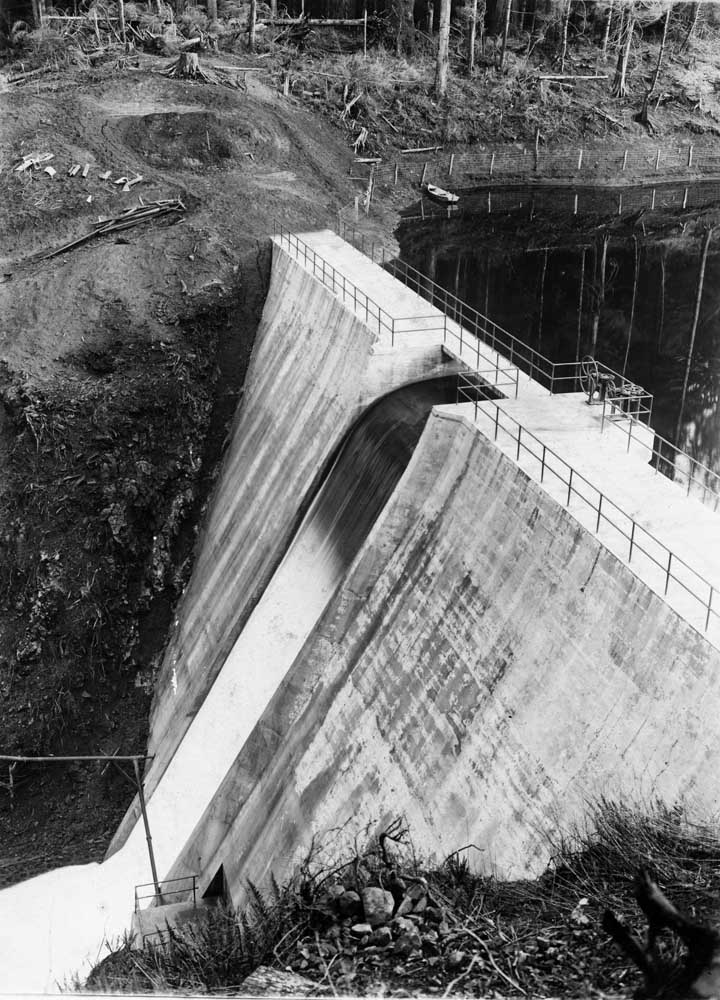

- A reinforced concrete dam was constructed in 1913.

BEAR CREEK WATERSHED — Maintaining Astoria’s multi-dimensional infrastructure is challenging: tens of miles of water and sewer lines, paved streets and wood piers wrapped on a dense, landslide-prone peninsula, beaten by heavy wind and rain, in one of the oldest cities of the West.

“This is a big, little city,” said Ken Cook, Astoria’s public works director. Cook says he’s impressed by the investment made by those who built the town, particularly those who thought to establish the water system and preserve the watershed surrounding Bear Creek Dam. The watershed supplies water to 10,000 customers in Astoria plus 5,000 more in nearby districts.

In 1895, the city of Astoria purchased Bear Creek Dam from Columbia Water Co. Work crews began immediately brushing out a route, through thick forestland, from the dam to Astoria. They hand dug a deep, 12-mile long trench, and constructed a 15-inch diameter, clamped wood water pipe within it. The pipe connected the impossibly small, stone dam to Astoria’s newly constructed Reservoir #2. By 1913, the dam was deemed inadequate. A new 82-foot tall, 200-foot long reinforced concrete dam was built. Forty years later, it was enlarged to 90-feet by 310-feet.

The wood water line was upgraded twice. Water is currently supplied through a 21-inch diameter pipe made of steel, but coated and lined with concrete.

Living in a house within the 3,700 acre watershed seems idyllic. It’s quiet. Elk, deer and an occasional bear may saunter passed within easy view. There is an opportunity for summer stargazing. And of course, just outside a window, there is the reservoir: a 200 million gallon lake in the forested foothills of Wickiup Mountain.

The work of Nathan Bartlett, the watershed’s caretaker, is hardly idle. To ensure water quality, he actively monitors and restricts public access to the watershed. Further, Bartlett checks the water temperature, its depth, turbidity and PH levels three times daily. “It can seem slow paced to others,” he explained, “but if something goes wrong, I have to fix it immediately… no matter what time of day or night.”

Bartlett has been at his job long enough to recognize seasonal changes in the water, too. This month, tannin from leaves makes water brackish. Yet, Bartlett says everything will change in January. “When it gets colder, it takes care of itself,” he said. “It’s just a cycle that it goes through.”

“I don’t have to do day-to-day maintenance of the dam,” he said, “but I do perform visual inspections.” Sometimes small leaks appear; Bartlett uses a snorkel lift to access them. Using a hammer and corking iron, he fills the gaps with lead wool.

The dam is in no danger of collapse, by the way. A recent geotechnical report confirmed the dam was constructed on firm ground. And an additional seismic failure analysis found the structure does not need additional modifications to meet today’s code. Its concrete, for instance, is three times harder than that currently required.

The watershed provides at least two eco-friendly, income producing opportunities. First, it earns the city 245,000 carbon credits. The city agreed to harvest only a third of the watershed’s annual growth. In exchange, its credits are sold to the Climate Trust. For the next 9 years, annual sales will contribute roughly $130,000 to the city coffers.

Second, a hydroelectric generator at the dam produces 154,645 kwh annually. Most of the electricity is used to power the water treatment system…a $9,000 annual expense. Excess energy — more than 50,000 kwh — is purchased by PacifiCorp, generating $2,200 annually for the city.

These and other public works projects were accomplished through relationships forged with public and private agencies. Cook estimates in the last 10 years, the city has received $40 million in grants to tackle Astoria’s infrastructure. He credits city staff. “I couldn’t do it without such a great team,” he asserted.

For more information about renovating an old home or commercial building, visit the Lower Columbia Preservation Society website at lcpsociety.com.