Central Oregon town pitches biomass to save forests

Published 4:00 am Sunday, August 22, 2021

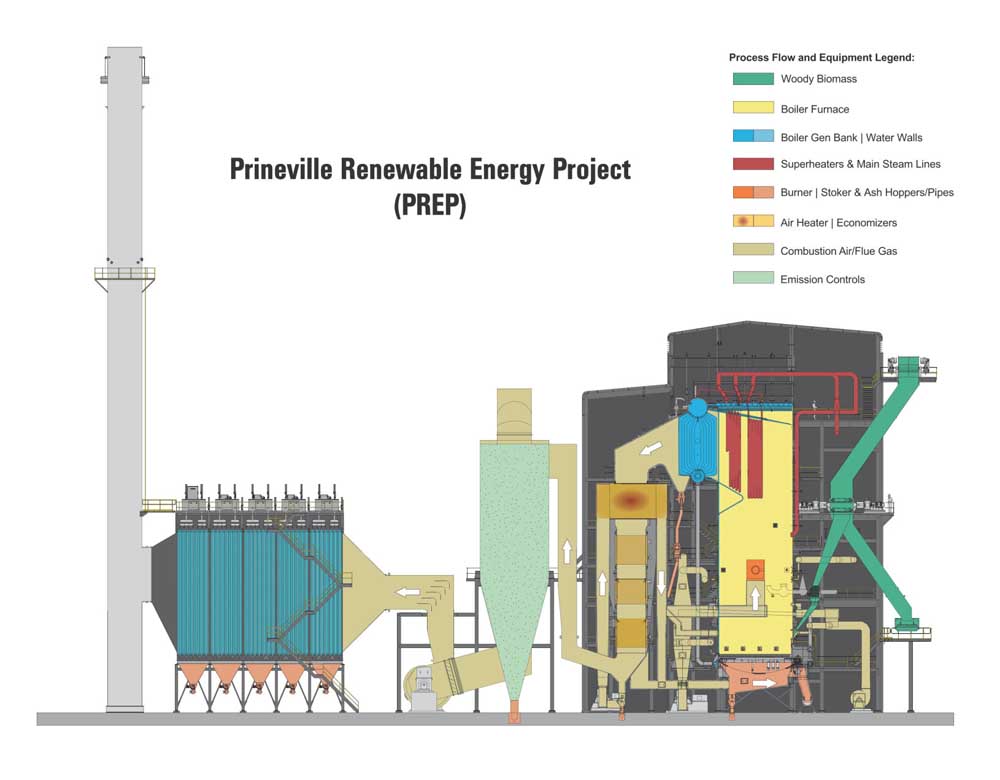

- The proposed Prineville Renewable Energy Project will use biomass collected from forests and other wood waste to create electricity.

Prineville wants to take the forest material that causes wildfires and use it to create electricity with a new biomass facility that could power more than 10,000 homes.

The estimated $120 million facility would burn biomass material from nearby forests and take in woody materials from sawmills or nut shells and turn them into energy. The project, however, is a ways away from becoming a reality.

In Oregon there are such 16 facilities that use organic waste, waste from wastewater treatment facilities or wood products from paper mills to generate electricity. Biomass is any organic material and can be burned and converted into electricity. One biomass facility in Marion County burns municipal solid waste.

Biomass facilities, while emitting some carbon, fit in with the state’s mandate of producing 50% of the power used by consumers from renewable resources by 2040, said John Cornwell, Oregon Energy Department senior policy analyst.

“Biomass facilities are typically located near the resources used to burn because there’s a cost associated with transporting the materials,” Cornwell said. “Often these facilities are attached to wood processing facilities or saw mills.

“But each project is unique.”

In Prineville, the concept is a passion project for City Manager Steve Forrester and Eric Klann, Prineville city engineer. Both have a background in forest products and both want to see the forest that surrounds Prineville, the Ochoco National Forest, preserved and protected.

“We’re just not managing a city,” Forrester said. “We have always been aware of the attributes of our forests, and we’ve always been interested in biomass as an energy producer. It makes sense in central Oregon.”

The design of the Prineville facility is being drafted and is funded by two grants: $150,000 from the Energy Trust of Oregon and $250,000 from the U.S. Forest Service, Klann said.

The city already has contracts in place to access private and public biomass supplies. The primary goal is to help the forest by clearing out debris, Forrester said.

“The project provides environmental stewardship for resources that are at risk because of a fuel load on the forest floor,” Forrester said. “We have to get in there and find a way to manage the forest. Our end game is to create something that other small communities could do as well. We think this is a revolutionary opportunity.”

The project aligns with the Forest Service’s Wood Innovations Grants Program that stimulates or expands wood products and wood energy markets to support the long-term management of national forest programs, according to its website.

“Prineville and Crook County are surrounded by pine and juniper forests on both private and public lands,” U.S. Sen. Jeff Merkley, an Oregon Democrat, said in an email to The Bulletin. “This makes it a prime area to study biomass and understand how it will benefit the environment by working with forest restoration projects to remove excess undergrowth and reduce the threat of mega fires.

“The biomass plant could also serve as a tool to manage the juniper population and help restore areas of sage steppe ecosystem with native grasses and revive dried out springs,” he said.

The project is in the early stages, said Dave Moldal, Energy Trust of Oregon senior program manager of the renewable sector. The nonprofit said the proposed biomass facility in Prineville is just the kind of resource it supports. It could take up to five years before the project is up and running, Moldal said.

The city also needs to find a utility or company to buy the electricity that’s generated. There’s a process that the city has to go through with Pacific Power, said Tom Ganaut, company spokesman. The electricity generated needs to be connected to the grid.

“We’ve spoken with Prineville over the years that they’ve contemplated this,” Ganaut said. “It’s early it the project.”

At one point La Pine had been considered as a site for a biomass facility. Biogreen Sustainable Energy, a St. Helens-based company, had submitted plans and been approved by Deschutes County in 2009 for a biomass facility at the La Pine industrial site. But the facility was never built because of infrastructure issues, said La Pine City Manager Geoff Wullschlager.

It was going to generate more than 24 megawatts of power by burning woody debris harvested from the 26,000 acres of private forestland the company owned about 30 miles southeast of the city, according to news reports.

The last biomass facility that was built in Oregon was in 2019, Cornwell said.

“The Environmental Protection Agency continues to recognize the importance of the nation’s forest resources and related industries, and the role that biomass can play in tackling the climate crisis,” Mark MacIntyre, EPA senior public information officer, said in an email. “Conservation and responsible management of resources can help ensure our forests and other lands will continue to remove carbon from the atmosphere while also improving soil and water quality, reducing wildfire risk and enhancing forests’ resilience in the face of climate change.”

Biomass is one of many different kinds of renewable energy, Cornwell said. There’s solar and wind, both of which are variable, but biomass can burn 24/7 and is considered a reliable source of alternative power. In Oregon, renewable energy accounts for 20% of the electricity generated. By 2050 that number must grow to 40%, according to recent legislation.

“There’s a substantial need for clean energy resources,” Cornwell said. “A biomass facility like this one would be an asset.”