How young is too young to marry? Any age under 18, says a bill before the Oregon Legislature

Published 8:31 am Friday, February 21, 2025

Oregon’s 17-year-olds aren’t old enough to vote. Or buy a pack of cigarettes.

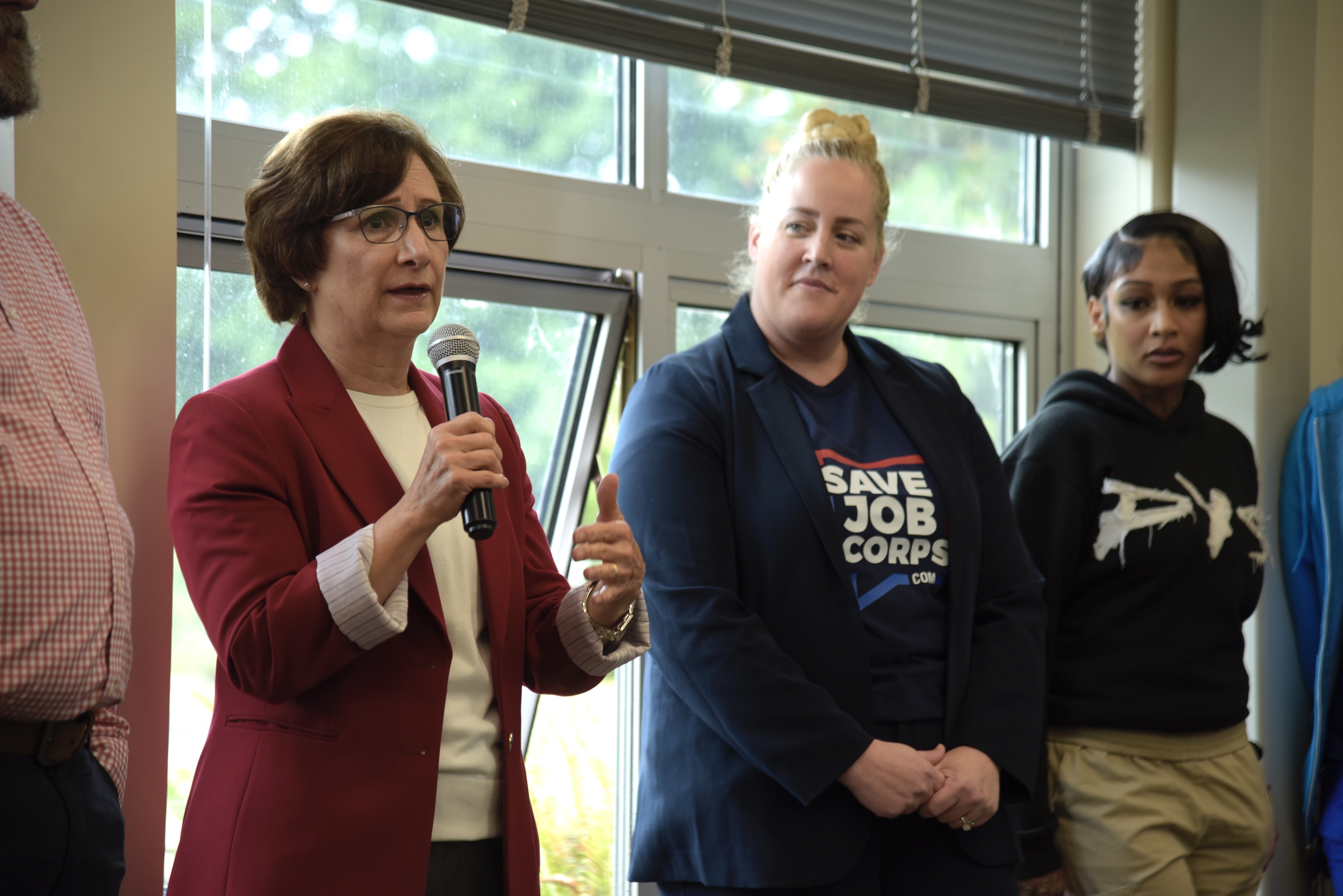

“But a 17-year-old is allowed to go to the chapel and get married,” Sen. Janeen Sollman told a legislative committee Wednesday.

Sollman, a Hillsboro Democrat, has teamed up with two of her Republican colleagues to sponsor a bill she says they all agree upon: Raising the minimum marrying age in Oregon to 18 with no exceptions. Currently, 17-year-olds can marry if one of their parents consent, and parents don’t always act in their children’s best interests, Sollman said.

“The research shows that children, especially girls, who are married under the age of 18 are more likely to experience poverty, domestic violence, high-risk adolescent pregnancies, mental health and substance use disorders and often have limited opportunities for educational and career advancement,” Sollman told the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Sollman said many marriages of teens 17 and younger are to older men, and they may be forced into human trafficking.

Some states, including Idaho, allow children as young as 16 to marry with a parent’s consent. Kansas sets the age as young as 15, with a judge’s approval. Other states, California among them, have no minimum age as long as a parent and a judge approve.

Eleven states, including Washington, have raised the minimum marriage age to 18 with no exceptions, according to the child advocacy organizations United Nations Children’s Fund and Unchained at Last.

While Oregon law allows 17-year-olds to marry with a parent’s approval, it doesn’t allow them a way out, Sollman said.

“Even those who attempt to leave the marriage are not allowed to file divorce as a minor, and (they) often struggle to protect themselves, leave home, access shelters and file protective orders,” Sollman said.

Advocates for raising Oregon’s marriage age said parents can force 17-year-olds to marry for various reasons, such as wanting to comply with social or cultural norms or wanting to end any financial obligations to support the child because those requirements disappear when the child marries. Michele Hanash, from the national women’s advocacy organization AHA Foundation, told members of the committee that a 17-year-old doesn’t have to consent to marriage in Oregon, only their parent does. Advocates say they’ve talked to child brides who sobbed because they didn’t want to marry.

Senate Judiciary Chair Floyd Prozanski, a Democrat from Eugene, asked why a judge, clergy member or other person would officiate at a wedding if a young bride or groom was unwilling to say “I do.”

“If I was officiating that wedding, I’d be like, ‘Well, this isn’t happening,’” Prozanski said. “Not that I would do one (a ceremony) for a 17-year-old.”

Hanash said children can be coerced into going along with marriage, even though it’s not what they want.

“They were too scared to speak up,” Hanash said.

Amy Turpin told the committee that as a teen growing up in Marion County she married an older man, eight years her senior, who devastated her life.

“I got married at 17, but I had his kid at 16. I met him at 15,” she said. “All of which should have been illegal, but because he was a great guy and stuck around to marry me, I didn’t really see any other option.”

Turpin also said her family approved of the marriage because underage marriage had been the norm, with her mother and grandmother also marrying young.

“My life is a testament to everything you’ve heard so far about this,” Turpin continued. “I didn’t get to graduate high school because I had a C-section during finals week. He moved me out of state immediately before I was 18, so I was isolated and trapped.”

She said her husband went to the bank on the first day it was open after their wedding and withdrew all of the money from her account.

“Every worst-case scenario you can imagine has probably happened to me since then,” Turpin said, adding that she eventually was able to leave that life behind and now is in “a safe place.”

In addition to Sollman, a Democrat, Senate Bill 548 also has garnered the chief sponsorship of Sen. David Brock Smith, a Port Orford Republican, and Sen. Kevin Mannix, a Salem Republican. Eighteen other legislators have signed on as sponsors.

No one testified in opposition to the bill.