Weekend Break: Oregon’s lost coastal city

Published 3:00 pm Friday, March 19, 2021

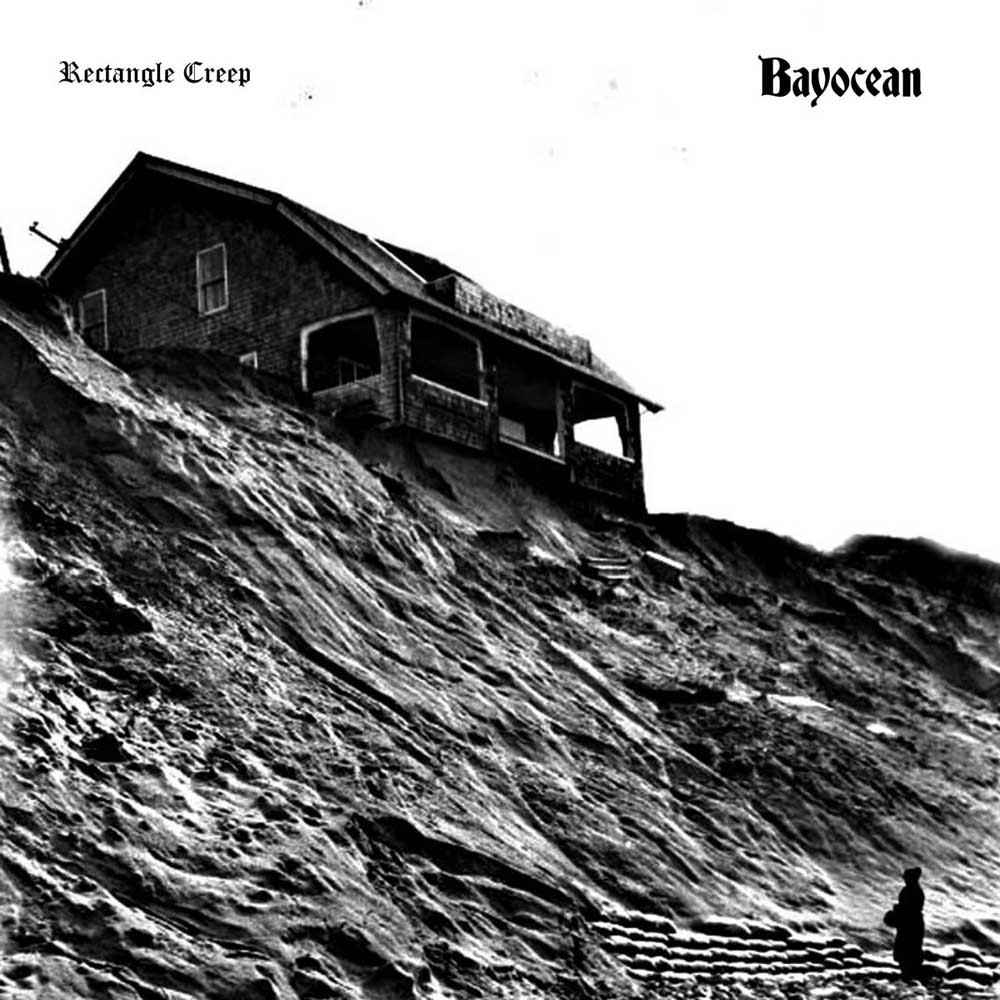

- Rectangle Creep released a 22-track album retelling the story of Bayocean.

Although he lives in Maryland, musician Matt Cutter is intimately familiar with a little-known piece of Oregon’s history: the rise and fall of Bayocean.

Trending

His band, Rectangle Creek, released an eponymic album about the city in June. Cutter discovered the so-called “city that fell into the sea” while researching for a speculative fiction novel he wants to write about post-ecological collapse in the U.S.

Bayocean was once a resort city on a peninsula between Tillamook Bay and the Pacific Ocean. The peninsula is now covered with brush, with few remaining clues about its history.

“It is literally a ghost city because there is nothing left of it whatsoever,” Cutter said. “It’s all just flat and smooth for miles and miles. (There is) literally no trace of this town but it’s amazing that there was a natatorium — a huge indoor, steam-powered wave pool with a 1,000 seat movie theater. They were trying to build an Atlantic City on the West Coast.”

Trending

Bayocean has all the makings of a compelling saga: rich investors, luxurious amenities, fearsome natural forces, persevering figureheads and inevitable destruction. It is the tale of how a once extravagant resort destination eroded away a few decades after it was built.

‘The Atlantic City of the West’

In 1906, well-established real estate promoter Thomas Benton Potter stumbled upon a stretch of beach between Tillamook Bay and the Pacific Ocean. Potter decided to build a resort community on the land.

Potter and his son, T. Irving Potter, built dozens of lots, recruited buyers and contracted with other developers to erect what they envisioned would become a “playground for millionaires.”

By 1914, roughly 2,000 people lived in the resort city. Dozens more vacationed there in the summer.

One of the first people on record to buy a plot was Francis Drake Mitchell, who eventually became synonymous with the city. He built a general store and the Bayocean Hotel. His wife served as the city’s postmistress. The couple was the last to leave the city when it met its fate decades later.

Some minor coastal landscape erosion was reported in Bayocean’s early years. Beach erosion did not threaten the city in a dire manner until 1914, when citizens decided to stabilize and improve safety of the mouth of the Tillamook Bay — thus sealing the city’s demise.

At the time, Bayocean did not have a road connecting to the mainland. Visitors instead arrived by way of a steamship called the S.S. Bayocean. The three-day trip became particularly unpleasant as the yacht neared the unprotected mouth of Tillamook Bay and contended with rough waves.

Citizens turned to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for a solution in the form of a jetty.

Usually, jetties are built in pairs to prevent inadvertently creating damaging cross currents. Bayocean, however, could not afford to fund both jetties. Despite the Corps’ strong recommendations against doing so, the city proceeded with building one jetty.

The 5,600-foot structure jutting out of the north end of the bay was completed in 1917.

Losing coastline, fast

The singular jetty caused “drastic fluctuations of wave patterns” and dramatically accelerated beach erosion. Historic accounts detail residents’ reports of portions of their front yards regularly washing out. Others moved their summer cabins inland for safety. One man lost his home completely. He couldn’t find the structure during a vacation because it had fallen into the ocean.

In his research on Bayocean, Oregon historian Jerry Sutherland noted that the “destruction became a tourist attraction of its own” and some vacationers would visit to take photos of “houses hanging on the edge of the dune.”

Around 1928, the group managing the city built a road to the spit from Tillamook.

Four years later, a large storm crossed the beach and destroyed the city’s natatorium wave pool. Around the same time, the Corps began extending the jetty.

The additional length exacerbated the erosion. By 1950, more than 20 homes had fallen into the ocean. Bayocean’s landmass was noticeably smaller. Often, the road onto the spit would washout, temporarily stranding the city from the mainland.

The Potters had long abandoned the resort city to pursue other projects, leaving residents to deal with the erosion.

Mitchell stepped in, appointing himself as protector and spokesperson for the city. He continued to lure vacationers to the island, despite a growing lack of luxury. When winter storms washed out roads, Mitchell and his wife would use “a wheelbarrow full of sand and rocks and a shovel trying to shovel back in the land and prevent erosion,” Cutter said.

There was little one man could do to combat the forces of nature. In 1952, a huge breach occurred, entirely cutting Bayocean off from the mainland. That same year, Mitchell’s wife suffered a stroke. The couple left Bayocean to seek medical help. They never returned. Mitchell’s wife died. He was sent to Oregon State Hospital in Salem by court order. Some reported he was driven mad by his failed pursuit to save Bayocean.

The Corps eventually built a second jetty in the early 1970s and most of the erosion stopped. Today the spit is managed by Tillamook County. Visitors can walk the beach, hike trails and picnic. Little evidence of the once extravagant resort city remains.

Crafting the album

Cutter said he wants Rectangle Creep’s “Bayocean” album to increase awareness of the true cautionary tale of interfering with natural landscapes without proper research. He wants listeners to remember that human actions have consequences.

“I would hope for people to see … how easy it is to mess with your surroundings with something as innocuous as building a jetty — then all of the sudden you are literally watching the land slide away before your eyes,” he said. “I really think that climate change is going to reach that point unless people are willing to recognize that things are definitely happening, even if you don’t perceive them happening incrementally.”

Cutter based most of the album’s lyrics on extensive research he conducted about the lost resort city. Some of the songs, though, add a dramatized reimagining of history, Cutter said. For example, in one song about the Potters, Cutter sings, “Go get the Buick and load up the shotgun,” referencing a potential business deal.

“TB Potter, the elder developer, and his son … were definitely pretty ruthless land developers. The son was the bulldog that would go in there and make the hard sell,” Cutter said. “But as far as I know they weren’t into any serious mafia leg breaking … That was all just to inject a little drama into the proceedings.”

Cutter said he makes music for fun, not fame but he does envision one day striking it big enough to gather his bandmates for a trip to Oregon, where they could perform live before an audience in honor of Bayocean.

“We joke amongst ourselves that maybe when our record goes platinum, they will invite us to the Bay City Arts Center to play a show,” Cutter said. “That would be a dream, to be able to put together a whole libretto and show around that record and perform it in Bay City.”

Listen to the album:

“Bayocean” by Rectangle Creep

Online album available at https://rectanglecreep.bandcamp.com/album/bayocean

Visit the Spit:

Bayocean Peninsula Park

North Hwy 131, Tillamook, OR 97141

(Located on Bayocean Road and Bayocean Dike Road in Tillamook, just east of Cape Meares_

$10 Tillamook County Day Use Access Parking Fee