County, state wrestled over response to Pacific Seafood outbreak, records show

Published 5:30 pm Thursday, December 3, 2020

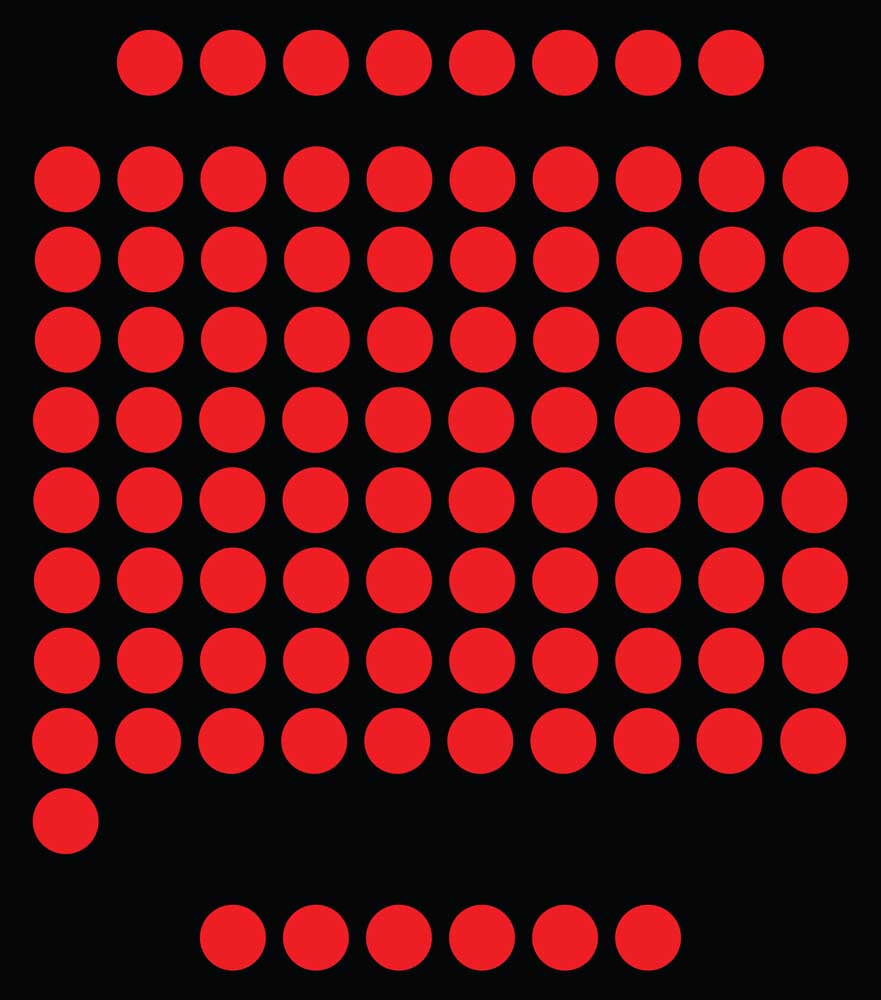

- A coronavirus outbreak among workers at Pacific Seafood in Warrenton in September was tied to 95 virus cases.

Michael McNickle, Clatsop County’s public health director, sent an email on the morning of Sept. 24 to top administrators at the Oregon Health Authority.

The subject line said it all: “Pac Seafood HUGE outbreak”

“Clatsop County is requesting an emergency meeting to discuss the massive outbreak — in terms of a small coastal community — of 77/159 workers at Pacific Seafood — which is only the night shift,” McNickle wrote. “We need to discuss closure of the facility, contact tracing the number of folks positive, quarantining plans and so forth.

“Our expectation is that OHA is the lead on this as this was agreed to in June.”

That afternoon, County Manager Don Bohn sent a follow-up email to the Oregon Health Authority after learning the onus for contract tracing, quarantine and wraparound services for the outbreak at the Warrenton seafood processor was being redirected to the county.

“However we decide to move forward, I would appreciate the opportunity to discuss, brainstorm and ideally coordinate information, resources and efforts,” Bohn wrote. “Who is the best person on the OHA team to coordinate this liaison function? At this point, the county does not have the information necessary to springboard into our response.”

The emails, obtained by The Astorian through the Oregon public records law, show the behind-the-scenes uncertainty during the response to the county’s largest workplace outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic.

Pacific Seafood tied the outbreak to 95 virus cases, making up about 24% of the 400 cases disclosed by the county since March. The seafood processor temporarily suspended operations at the Warrenton plant. The Warrenton-Hammond School District, which had just opened the new school year, abruptly closed schools. The outbreak, along with a surge in virus cases after the Labor Day holiday, pushed the county on to Gov. Kate Brown’s statewide watch list.

Workplace outbreaks at seafood processing plants account for a disproportionate share of the county’s virus cases. But even after managing through outbreaks during the spring and summer at Bornstein Seafoods, Da Yang Seafood and Pacific Seafood — and clashing with Pacific Seafood over how best to respond — emails show the county was unclear about the chain of command and the role of state regulators when the new outbreak hit Pacific Seafood in late September.

The emails also reveal frustration among staff at the county’s Public Health Department over the distinct treatment Pacific Seafood — a dominant force in the West Coast fishing industry — received from the state. Over the summer, after Pacific Seafood resisted the county’s calls for workers potentially exposed to the virus to quarantine, the Oregon Health Authority took the lead in responding to workplace virus cases at the Warrenton plant.

But the arrangement, which the county had described as a joint decision with the health authority, caused confusion in the critical hours after the new outbreak.

Under the strain of responding to the pandemic and the wildfires that burned across Oregon, the health authority initially urged the county to explore mutual aid options with other counties and offered a handful of contact tracers. After Bohn pushed back, the health authority clarified the roles.

“OHA will own the outbreak,” a health authority program manager wrote of the first batch of Pacific Seafood virus cases from the plant’s night shift. The county would take the lead if a second batch emerged after workers from the plant’s day shift were tested.

“We will be ready to do our part,” Bohn wrote. “I appreciate the partnership.”

‘So … are we surprised?’

The Astorian sought the emails and other documents to examine the county’s response to the Pacific Seafood outbreak. In the days after the outbreak, McNickle said the county was not aware of what steps had been taken by the seafood processor or the health authority after a worker at the Warrenton plant tested positive for the virus in early September.

The newspaper filed the request for information under the public records law to help better understand the timeline.

The emails, though, do not shed new light into what extra precautions — if any — were taken in the two weeks between the one positive case and the outbreak. Instead, the records illustrate tension between the county and Pacific Seafood that had been building over the spring and summer and county staff’s skepticism of the health authority’s leverage with the Clackamas-based seafood giant.

In early June, McNickle had called for mandatory virus testing of essential workers and more frequent state inspections after outbreaks at Bornstein Seafoods in Astoria and Pacific Seafood in Warrenton. The Astorian, through the public records law, learned the county and Pacific Seafood had clashed during an outbreak in May over whether the close contacts of workers who tested positive had to self-quarantine for 14 days. That outbreak was linked to 15 virus cases.

A similar dispute erupted in late June and early July after a Pacific Seafood worker from Moldova who was in the country under the federal H-2B visa program tested positive for the virus. The Oregon Health Authority took over the lead in responding to workplace virus cases at the Warrenton plant after the disagreement.

Since it was unusual for the county Public Health Department not to take the lead on local workplace outbreaks, the county, the health authority and Pacific Seafood worked on an agreement over the summer on how to respond to future virus cases.

After learning of new cases at Pacific Seafood in September, McNickle reached out to the health authority to ask whether the seafood processor ever signed the agreement.

“No, we didn’t land it,” a health authority program manager wrote back. “We went through two rounds of revision with PS and were close, then fires and now new cases …”

“So … are we surprised?” McNickle asked his colleagues in county public health and emergency management.

“Sadly, no,” a public health staffer responded.

‘… as you probably know’

Pacific Seafood and other seafood processors are considered essential to the nation’s food supply, so workers have been able to stay on the job during the pandemic. The Oregon Department of Agriculture regulates food processors, while the Oregon Occupational Safety and Health Administration enforces workplace safety.

According to Pacific Seafood, the Department of Agriculture led audits of the Warrenton plant twice in July to verify compliance with virus prevention measures.

Oregon OSHA has been under scrutiny statewide over a lack of inspections, but, in fairness to the agency, their actions are based on complaints or referrals from state and local authorities.

Earlier this year, The Astorian reported that the Lower Columbia Hispanic Council — now Consejo Hispano — had filed a complaint with OSHA on behalf of workers at Bornstein Seafoods before an outbreak was linked to 33 virus cases. OSHA, which never inspected Bornstein Seafoods, found sufficient evidence that the conditions described in the complaint had been corrected or no longer exist.

An anonymous complaint against Pacific Seafood in May claimed workers at the Warrenton plant were being required to return to work after testing positive for COVID-19, The Oregonian reported. The complaint was resolved without an inspection.

The Oregonian has reported that state officials received warnings before 23 of the 35 largest workplace outbreaks during the pandemic yet inspected only two of the businesses before the outbreaks and found no violations.

Emails obtained by The Astorian show McNickle flagged the Pacific Seafood outbreak in September with Michael Wood, the administrator at Oregon OSHA. Sharing the state’s playbook for responding to outbreaks, McNickle wrote, “it appears OSHA has a major role when a food processor has positive COVID cases” and asked what the agency had found after inspecting Pacific Seafood.

Wood explained OSHA’s role in his response to McNickle. “We do not actually inspect under the playbook,” he wrote. “Unless we receive a clear enforcement referral from local public health or OHA we do not initiate enforcement activity based upon an outbreak report.

“We also can do that in response to complaints, but as you probably know we have not received a complaint in re Warrenton since the single complaint we received in May.”

‘This makes me sick’

Pacific Seafood has a comprehensive COVID-19 safety plan and resource guide to help prevent the spread of the virus among workers.

Rather than rely on the county, Pacific Seafood supervised worker testing through a private laboratory during the outbreaks at the Warrenton plant in May and September. Emails show the seafood processor has vigorously defended the ability to keep workers who may have been exposed to the virus from missing shifts on the processing line, citing federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for critical infrastructure workers.

Pacific Seafood has also tried to counter the idea that workplace outbreaks are evidence of workplace spread of the virus. The company’s director of legal and government affairs, in an email to U.S. Rep. Suzanne Bonamici’s office after the outbreak in September, said, “There appears to be some confusion about the facts, which unfortunately likely stems from Oregon’s unique way of attributing positive cases to employers even absent evidence of workplace spread.

“In this case, there is no evidence of that.”

Pacific Seafood’s narrative about the September outbreak dovetailed with McNickle’s description of community spread of the virus after the Labor Day holiday. The public health director said visitors to the North Coast during the holiday weekend did not always practice social distancing and wear masks and participated in large gatherings. He also blamed what he called “COVID fatigue” after months of virus precautions.

In the email to the congresswoman’s office, Pacific Seafood outlined the 95 virus cases in the outbreak: eight initial cases; 81 in the first batch of testing night shift workers and workers who were living in a local hotel; and six cases in the second batch of testing day shift and other workers.

The seafood processor traced the eight initial cases to a Labor Day barbecue and tied the vast majority of other cases to workers living at the hotel.

Pacific Seafood’s narrative — distancing the outbreak from the Warrenton plant and focusing on Labor Day social activities — grated on some local political leaders and social service advocates.

Several privately complained to The Astorian that seafood workers in quarantine were not getting adequate care and support and the company and the Oregon Health Authority were not providing enough information. Warrenton Mayor Henry Balensifer was especially critical of the state and what he characterized as the special treatment for Pacific Seafood.

“Pacific Seafood details outbreak at Warrenton plant,” a headline from The Astorian read.

A county public health staffer shared a link to the story in an email to her colleagues in public health and emergency management. The subject line: “This makes me sick”

Saying she was “deeply concerned,” Bonamici urged the Oregon Health Authority and Pacific Seafood to hold a virtual community meeting to answer questions from the community.

At the town hall, Patrick Allen, the director of the Oregon Health Authority, said there was no plan to retest Pacific Seafood workers for the virus at regular intervals, since serial testing is not something supported by data as being useful.

Clatsop County would end up recording 125 virus cases in September. The vast majority were linked to Pacific Seafood.

‘We need to say something’

Days after the Pacific Seafood outbreak, in a meeting with The Astorian, County Manager Bohn announced that he wanted the county to take the lead in responding to any future outbreaks at the Warrenton plant.

Emails show that while there was still frustration among county public health staff, the county recognized the need to have a working relationship with one of the region’s largest employers.

“Staff feel like we need to say something — but we also need to say in a way that allows us to move forward in partnership with the company,” Bohn wrote to Commissioner Kathleen Sullivan and Commissioner Mark Kujala, while sharing talking points for the meeting with the newspaper. “We are committed to improving our working relationship and are ready to move forward in a positive direction.”

At the meeting in early October, Bohn discussed working with Pacific Seafood on the agreement that had stalled over the summer. The memorandum of understanding would not be signed by Bohn and Dan Occhipinti, the executive vice president of corporate support for Pacific Seafood, until late November.

The agreement covers three main areas: prevention; testing, reporting and notification; and contact tracing and quarantine.

On quarantine — the issue that caused previous clashes — the agreement allows workers who are potentially exposed to the virus to continue working if they do not have symptoms. Workers who live with someone who tests positive have to quarantine for 14 days.

The county and Pacific Seafood also agreed not to publicly disclose virus cases at the Warrenton plant unless they reach the threshold for disclosure of workplace outbreaks by the Oregon Health Authority, which is five cases. “This includes, but is not limited to, disclosing Pacific’s name, or references to Pacific such as ‘large seafood processor’ in public meetings or in response to media inquiries,” the agreement states.

Both Pacific Seafood and the county have publicly disclosed individual virus cases at the Warrenton plant and could still do so under the agreement if all parties agree. The Astorian and others have urged the county Public Health Department to disclose when there is the potential risk for a workplace outbreak that could lead to dozens or hundreds of new virus cases.

“The county is prepared to partner closely with Pacific Seafood, OHA and any number of other agencies in response to any potential future outbreak,” Bohn said in an email in response to questions from The Astorian about the county’s preparation. “The county is fortunate to have a highly skilled and experienced public health staff ready to take the lead.

“The underlying principles of the MOU have already fostered an improved working relationship between Pacific Seafood and county staff. We are communicating effectively and are ready to come together to address any manner of situation or concern.”

Bonamici said “local public health officials like the Clatsop County team have been working hard in unprecedented circumstances to contain this pandemic, and I applaud their efforts.

“After I called for a community meeting during the Pacific Seafood outbreak, the state and the company acted quickly to provide a forum for community members to ask questions and receive information,” the Oregon Democrat said in an email. “I appreciate their responsiveness and I’m glad that Pacific has reached an agreement with Clatsop County to strengthen the ongoing effort to keep our community safe and healthy.

“As cases surge, we must all follow every public health guideline and do our part to save lives and contain this devastating virus.”

A workplace outbreak of the coronavirus at Pacific Seafood in Warrenton led to 95 cases, the largest in Clatsop County during the pandemic.

The Astorian sought emails and other documents through the Oregon public records law to examine the county’s response.

Let us know what you think in a letter to the editor: bit.ly/2kuT0PZ