Moonshine memories: Rip-roaring era began a century ago

Published 9:11 am Friday, November 1, 2019

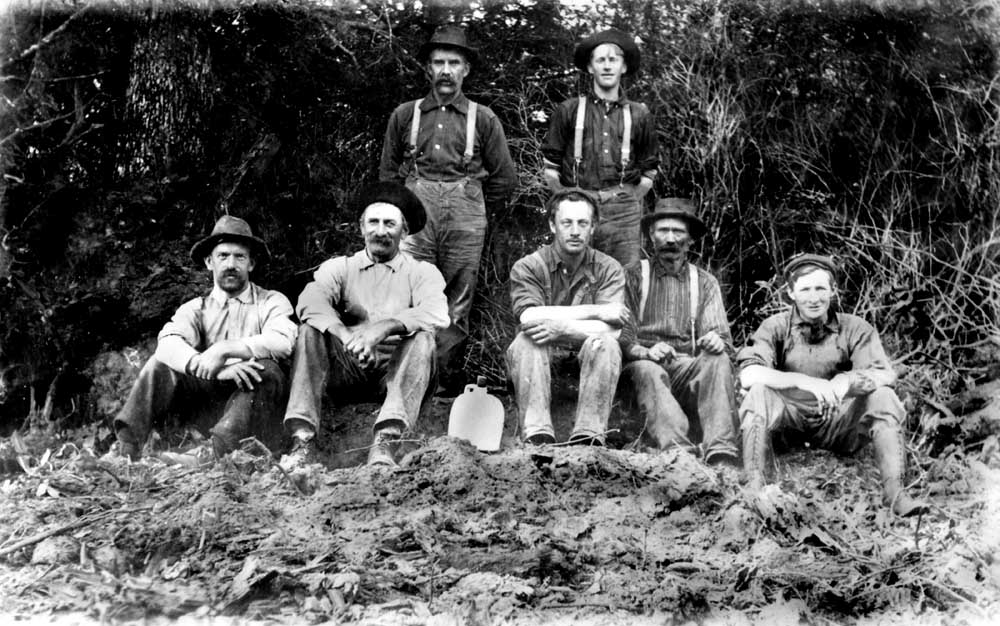

- Prohibition was probably never popular among Southwest Washington’s hard-working men, including these in south Pacific County, who were evidently sharing a jug back around a century ago.

Amateur historians and cocktail fanatics alike can raise a rather ironic glass to toast one of America’s most romanticized law enforcement flops. This fall marks the 100th anniversary of the National Prohibition Act, but the cat-and-mouse game between moonshiners and sheriffs began a couple years earlier in Washington state.

The Volstead Act (sometimes called the National Prohibition Act), which outlined how the U.S. would enforce the 18th Amendment prohibiting the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages, went into effect on Oct. 28, 1919, after the U.S. Senate overrode a veto by President Woodrow Wilson. That kicked off the Prohibition era that fueled bootlegging operations and glamorized the American gangster.

Washington state got a two-year head start on Prohibition when it passed the 1917 “bone-dry” law outlawing alcohol. Oregon voters banned the manufacture, sale or advertisement of intoxicating liquor on Nov. 3, 1914, five full years before the rest of the nation. Seattle went dry on Jan. 1, 1916, one of the first large American cities to do so.

‘It was a very vocal minority that pushed for [Prohibition] to happen. Maybe we should have listened to the community more.’

Cowlitz County Undersheriff Darren Ullmann

But banning alcohol only seemed to make it more popular because, as Cowlitz County Undersheriff Darren Ullmann puts its, alcohol is as American as baseball and apple pie.

“We use alcohol in celebration, and we glamorize its use. … The more they tried to suppress it, the more criminal activity that bubbled to the surface,” said Ullmann, who published an essay on law enforcement’s dealings with alcohol in the Cowlitz Historical Quarterly in 2013.

“It is hard to find a newspaper without an article about a bust of alcohol in the 1920s and 1930s,” he said.

Good country for stills

Southwest Washington geography — with thick forests and easy access to water — lent itself well to illicit liquor distillation. All you needed was a still, preferably a “very small and very portable” contraption that could be disassembled and fit in a backpack, said John Koehler, owner of the Longview-area Eagles Cliff Distillery. (Koehler researched the history of distilling before he and his wife opened their potato vodka business in 2016 west of Longview.)

“When they got out into the woods, they would run a hose from a nearby creek for their operation, build a fire and distill their product right there,” Koehler said. “Then they’d take the end product and haul it back out so they could sell it.”

Some area bootleggers probably used “thumper” stills, which make a thumping sound as the gases build up pressure and “come burbling through” the device, Koehler said.

“The old-time bootleggers were so good at this that they could sit there and listen to the thumper making its noise, and they could tell you within a couple of proof what the proof of the product would be when it got done,” Koehler said.

Nearer the mouth of the Columbia, the easy transportation corridor from Canada created opportunities for rum runners.

In September 1916, nine months into Washington state’s prohibition, with suspiciously complete knowledge the Chinook Observer reported on one of many, many smugglers:

“A whiskey vendor is doing business outside the Columbia River bar, on a ship named Tramp. He is selling ‘barbed wire whiskey’ in solution at $1 a quart, bonded goods at $2 a quart, and beer at 33-1/2 cents per bottle. The federal authorities are waiting to swoop down on Skipper Bob Jones and his whiskey ship, and if they lay hold of him they will probably prosecute him on a charge of ‘maintaining a general nuisance.’ Fishermen, gillnetters, and Astoria businessmen are said to be patronizing the booze skipper. He hails from Eureka, Cal.”

‘You ain’t coming back’

Back in the 1980s, historian Marie Oesting made a valiant attempt to capture the recollections of Pacific County locals who knew anything about those times. Although people may claim to appreciate having a colorful horse thief in the family, Oesting encountered a great deal of reticence when it came to speaking on the record. Maybe the same moralist streak that led our ancestors to implement the ban on alcohol constrains their descendants from admitting grandpa profited from trafficking rotgut liquor.

One of her best interviews was with “Slub” Tenho Harju, a tremendously nice man on the Peninsula, now dead, with a neck like a keg of bolts. He told her a variety of hearsay stories that wouldn’t stand up in court, but make for good reading. One was from his cousin, who used to be invited to ride along with a deputy who lived nearby.

“On one of those trips they were looking for a still that was reported in the area, and they was just going out in the woods and they’d find where there was a little stream, and they’d head up the stream you know and see if they could find anything,” Slub reported, noting that stills require a lot of fresh water. After wasting quite a few hours bushwhacking their way up creeks and not finding anything, his cousin suggested to the sheriff that they check out a little bigger creek. “And he drove by the place. He [the cousin] says, ‘Right here; here, stop here.’ He [the sheriff] says, ‘Can’t go up there, kid, there’s b’ars up there.’” In other words, he knew where the still was, but he wasn’t going to help the deputy find it.

Slub remembered a friend whose father was a reputed bootlegger. “And this kid was around their home place, you know, it was on the road between here [Ilwaco] and South Bend, and he, the sheriff and some other fellows came along. ‘Your dad at home?’ ‘Nope.’ He says, ‘Is he out in the woods?’ He says ‘Yup.’ ‘You know where he is?’ ‘Yup.’ They say, ‘Will you take us up there?’ He says ‘Nope.’ ‘Give you 50 cents to take us up there.’ ‘Nope.’ When their offer got up to $10, he says ‘OK,’ $10 being a lot of money in them days. So he [the sheriff] says, ‘Let’s go.’ He [the kid] says, ‘Pay me.’ Sheriff said, ‘We’ll pay you when we get back.’ Kid shook his head. Kid says, ‘You ain’t coming back.’”

Official hypocrisy & foibles

It was, in some ways, an era of hypocrisy for law enforcement, Ullmann said.

“Saloons were your poor man’s social club, and the police back then weren’t rich,” Ullmann said. Police officers had the same problems of everyone else, and often the same solution: Drink those problems away.

When the federal government enacted Prohibition, police “enforced it because they had to,” but not necessarily because they all wanted to, Ullmann said. Some officers even ended up as moonshine makers themselves.

Federal agents in 1923 arrested then Kalama Town Marshal Ed White, former county deputy Bill Moon and others after a month-long undercover operation revealed the lawmen and their friends were bootlegging.

A colorful nugget in Oesting’s files came from Oysterville native son Willard Espy:

“You doubtless know the story … about the esteemed South Bend editor who became a high prohibition official but didn’t have much luck apprehending rum runners because he talked too much in bed to his mistress about what he was up to and she always told her husband, who was the chief rum runner. I don’t believe a word of it.”

The North Beach Tribune of July 3, 1925 delighted in reporting that the South Bend Journal editor, Frederick Archibald Hazeltine, “came down to be on hand for the smashing of the bottles [of seized Canadian liquor] but evidently did not stay long enough on the job for reports have it that the bottle breakers gave each sack a lick or two with a sledge and dumped the stuff overboard but partly broken. … As many as 30 cases are said to have been rescued by a single man and 50 boats were on the job so thick as to seriously interfere with one another.

“No doubt this will be a joyous fourth in Raymond and vicinity and Roy Herrold reports even the oysters of Willapa Bay are right up on their hind legs and the clams have developed a stretch in their necks of length and capacity beyond anything ever thought of heretofore.”

The total cargo was said to be in excess of 1,600 cases of liquor — precisely 18,836 bottles.

Noble cause fizzles

Born at the end of 1910, Espy was still a child when Prohibition came into force and just 22 when it ended.

“I do recall Saturday night dances at Long Beach,” Espy wrote, “When I was still in my early teens, at which the custom was for the young bucks to hide their bottles of lightning in the sand and go out to take a swig between swings around the floor.

“Roy Kemmer and I once spied on them, dug up their bottles, and managed to dispose of enough whiskey so that we were able to drive unscathed through a forest fire and then bump into a buried log on the ocean beach on the way home. Nobody hurt.”

This widespread disregard for Prohibition turned it into a big failure, and the states repealed the ban on alcohol with passage of the 21st Amendment in 1933. But the moonshine community endured.

Bootleggers continued to occupy law enforcement into the 1950s and 1960s, Ullmann said. And Koehler said there’s still a “very dynamic and active community” of home distillers today.

The memory of U.S. citizens’ pushback against Prohibition lives on in a rather romantic light. The gangsters were the heroes, Ullmann said, and the bootleg lifestyle seemed exotic and fun.

“It was a very vocal minority that pushed for [Prohibition] to happen,” Ullmann said. “Maybe we should have listened to the community more.”