Hemp gains ground among farmers

Published 1:11 pm Wednesday, April 10, 2019

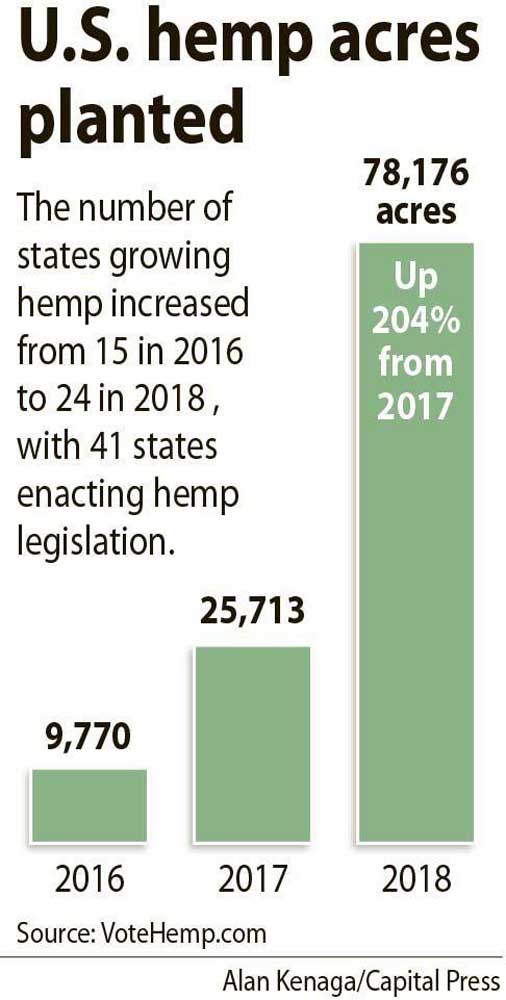

- Hemp graphic

Farmer Greg Willison and his son grew hemp for the first time last year near Coos Bay, and made money despite the many risks of raising a new crop.

“People need to keep in mind this is something you want to approach on small acreage, maybe 5 to 10,” said Willison, who is retired and lives in New Plymouth, Idaho.

Current and prospective growers of industrial hemp face many challenges in raising and marketing the controversial and high-priced new crop, which the 2018 Farm Bill authorized with the condition that states develop plans for managing it.

Even producers and researchers in states such as Oregon that studied the crop under pilot programs allowed under the previous Farm Bill say there are plenty of lessons yet to be learned.

“There is a lot of production knowledge that has not been established,” said Clint Shock, professor emeritus at the Oregon State University Malheur Experiment Station and horticulturist with Scientific Ecological Services in Ontario.

“Hemp will get there with scientific information, especially if industry supports that,” said Jay Noller, who heads Oregon State’s Department of Crop and Soil Science in Corvallis and leads the university’s hemp research.

Oregon State Extension will soon release new publications on hemp drawing on research the university has done.

Willison recently told an Idaho Legislature committee that a lack of chemicals approved for weed and pest control was an issue he and his son, Trey, encountered when they grew industrial hemp in Oregon.

Idaho lawmakers are debating a bill that would allow cultivation of the crop. The state Senate has already approved it.

Growing hemp

Noller said that as a new crop, hemp figures to enjoy lower pest pressure for a while and then will require more management.

“Gene flow” also comes up as an issue in hemp production, he said. Its pollen is small and can travel long distances.

Shock said hemp, like beans and onions, does not do well in soil with high salinity and pH levels.

The pH scale measures acidity. The higher the pH the less acidic soil is.

“If growers know their soils will grow beans and onions well, they will grow hemp well,” Shock said. “In areas where beans burn up, hemp will burn up.”

Hemp is also a poor choice in fields with large perennial weeds that can’t be cultivated out, he said. Yellow nutsedge, field bindweed, Russian napweed and whitetop are examples.

Noller said hemp “is not as thirsty as many of our irrigated crops.”

Growers can plant feminized seeds — which are bred to maximize flower production — start plants in a greenhouse before transplanting them to the field, or use clones. Approaches vary in cost and labor requirements.

Willison said clones produce the most stable field results but are the most expensive option. Even with feminized seed, pollen producers must also be planted, he said.

Depending on location, farmers may go with early-maturing varieties that are easier to harvest because they are dry, or aim for more flowers and cannabinoid content with later-maturing plants that require more labor and drying.

More lessons must be learned about what works best, where and for which customers, Shock said.

Have a plan

Willison said he and his son last year worked hard drying their crop, a key step in producing hemp.

As more farmers grow the crop for the first time, he recommends they have a plan.

“This year with oversaturation many people will lose a lot of money,” Willison predicted. “Write out a business plan and make sure you have done due diligence. Don’t be caught with a field of ripe flower in October and no place to dry it. … A drying facility should be created months ahead of time.”

Genetic purity and strength are critical, said Toby Feuling, who co-owns Hempbest Farms, a Waldport-based company that grows hemp in western Oregon and southwestern Washington state. Genetics should be selected based on heartiness for a region, market demand and overall crop viability, he said.

“There is not any reason to do anything without correct genetics,” he said. “I can’t stress that enough, because there were many farmers in Oregon last year who were not able to participate in sales this year because they did not buy the right seed.”

Feuling said he benefited from his previous experience raising medical marijuana starting in 2010 but worked hard at learning industrial hemp’s unique needs.

“The risk is very real, and in fact one of the biggest issues potential farmers face is finding reliable seed companies that have actually done field trials years in advance, or have a long-standing track record of providing seed that performs as claimed,” Oregon CBD co-owner Seth Crawford said.

His Willamette Valley company maintains strict standards for numerous quality measures, from genetics and hybrid vigor to a mid-September harvest regardless of location.

The shortage of reputable seed providers “is largely due to the fact that it takes years to develop good varieties,” Crawford said. “A lot of people are jumping in from the cannabis market right now and a lot don’t have the breeding background to produce quality.”

Many people from the cannabis market, producing marijuana allowed in many states, are accustomed to growing 100 plants at a time, he said.

“When you are growing tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of (industrial hemp) plants, you have very different requirements for stability and predictability you just can’t achieve in a single year throwing a couple of plots together,” Crawford said.

“We don’t apply the same growth techniques as medical marijuana,” said John Tucci, sales manager at Moses Lake, Washington-based HempLogic.

For example, spacing between plants should be much less.

“The reason for that is weed control,” Tucci said. “Each plant provides its neighbor shading. We have heard stories of spacing so far apart, and on larger grows, it’s hard to distinguish the product from the weeds themselves.”

He said HempLogic customers are asked what market they plan to grow for — such as CBD oil, fiber or grain — and to whom they plan to sell.

One challenge in growing for fiber is that there is competition from other countries with centuries of experience, Tucci said.

“Harvesting and drying are the biggest bottleneck in the industry,” said Oregon CBD’s Crawford, a former Oregon State public policy instructor. Seed “is very much a factor in having varieties finishing early in the season before the frost and rain really hit, giving farmers an advantage.”

Willison said Colorado and Oregon are the top producers of high-quality, feminized seed. Each seed can cost $1 to $5, depending on the quality and quantity purchased.

“Germination rates, CBD/THC (tetrahydrocannabinol) content and ratios can vary widely,” he said. “Know your seed producer. Visit their farm and make sure they are real.”

Hemp must have less than 0.3% THC, the substance in marijuana that makes people high.

International Hemp Exchange is based in Longmont, Colorado, and has seed production, farming and extraction operations throughout Oregon. It connects buyers and sellers across the supply chain.

It is a major supplier of feminized hemp seed around the world. Founder and President Mike Leago said the company’s breeding program has created a stable line of genetics high in CBD and low in THC.

In the growth cycle, it treats plants so they produce feminized seeds that become plants that devote most of their energy to producing oil and resin instead of seed production, which would occur if they were around pollinating males.

Strong demand

Leago predicted the supply of high-quality, feminized seed will not meet demand this year.

“We are having to say ‘no’ to some really high-volume requests so we can fill the needs of smaller American farmers looking to get into the hemp industry,” he said. That’s instead of selling all of its hemp seed to large corporations or commercial farms interested in buying the entire supply.

Seed supply and demand were about even a year ago, Leago said. Demand then started increasing steadily, until recently jumping due to hemp legalization via the new Farm Bill. He expects another couple of years during which demand grows faster than seed producers’ capacity to scale up production.

In the meantime, demand for CBD oil will likely continue to grow. Drug chains Walgreens and CVS just announced plans to start selling CBD products. “That should substantially increase demand as we see more and more brands start to integrate it,” he said.

Though hemp can be used to make fabric, building materials and other products, CBD oil is where most of the money is made. Hemp-derived cannabidiol — known by the initials CBD — is associated with many health benefits.

Feuling said breeders are also seeking to “breed up” levels of other cannabinoids, such as cannabigerol — known as CBG — and cannabinol — CBN — with an eye toward patenting seeds.

Total U.S. hemp industry sales were $820 million in 2017, the Hemp Business Journal reported, and topped $1 billion last year, when farmers in 24 states grew hemp.

Vote Hemp, an organization that tracks the industry, pegged the number of hemp acres grown at 78,176 last year, up from 25,712 in 2017. Montana and Colorado had the most hemp acreage.

So far this year, 751 Oregon farmers have registered more than 22,435 acres of hemp, according to the state, more than double last year’s total.

Different laws

Different states have different laws governing hemp.

Oregon’s thriving industrial hemp program allows CBD production, the main profit center for the industry.

Washington does not allow CBD production — a major factor limiting participation — but state Senate Bill 7256 now in the Legislature would allow it.

California passed a hemp-farming law but is still writing the regulations that would allow farmers in that state to grow the crop. CBD oil will not be part of the hemp regulatory program.

Idaho lacks any hemp program, but lawmakers were debating an amended bill as the Legislature approached the end of the session.

Oregon registers growers, handlers and agricultural hemp-seed producers. Gary McAninch, hemp program manager at the state Department of Agriculture, said a handler registration is required for CBD production, and a locally approved land-use compatibility statement must be submitted with the registration.

Buyers of end-use CBD oil that goes into their products do not need a handler registration as long as they obtain it from a registered handler.

McAninch said Oregon, which will update its rules per the 2018 Farm Bill, has been asking how much hemp is going to CBD. “But we are hearing almost all at this point in Oregon is being used to produce CBD oil or other extracts from the hemp plant.”

Willison said he and his son generated about $112,500 per acre in revenue growing for the CBD market last year.

He said a good crop produces about 2,000 pounds of hemp flower per acre for CBD extraction. It takes about 40 pounds of flowers to make a kilogram of CBD oil.

That comes to about 50 kilos of CBD oil per acre. They split that with the processor and sold their 25 kilos for $4,500 apiece. That’s a little more than $2,000 a pound, or $125 for an ounce of oil, a price that was holding as of early this year.

“CBD is by far the highest-value product,” Willison said. He expects the price to drop as acreage increases around the U.S. and some growers experience processing-capacity limitations. Hemp grown for fiber and seed for grain generate much less revenue.

Input costs for the Willisons were about $15,000 per acre, he said. From highest to lowest, they included labor, seed, nursery usage — to start plants off-site that are transplanted in the field — and an off-site drying facility.

In southwest Idaho, it has been common to generate $2,000 to $5,000 in revenue per acre for other crops, and spend 50% to 80% on inputs, Willison said.

Hemp’s input cost per acre could drop slightly over time as producers gain field experience and chemicals are developed and approved.

In the meantime, hemp is attracting a lot of attention from farmers as a crop that may be worth the many risks involved in growing it.