The prisons of Mandela and Napoleon

Published 11:00 am Friday, February 15, 2019

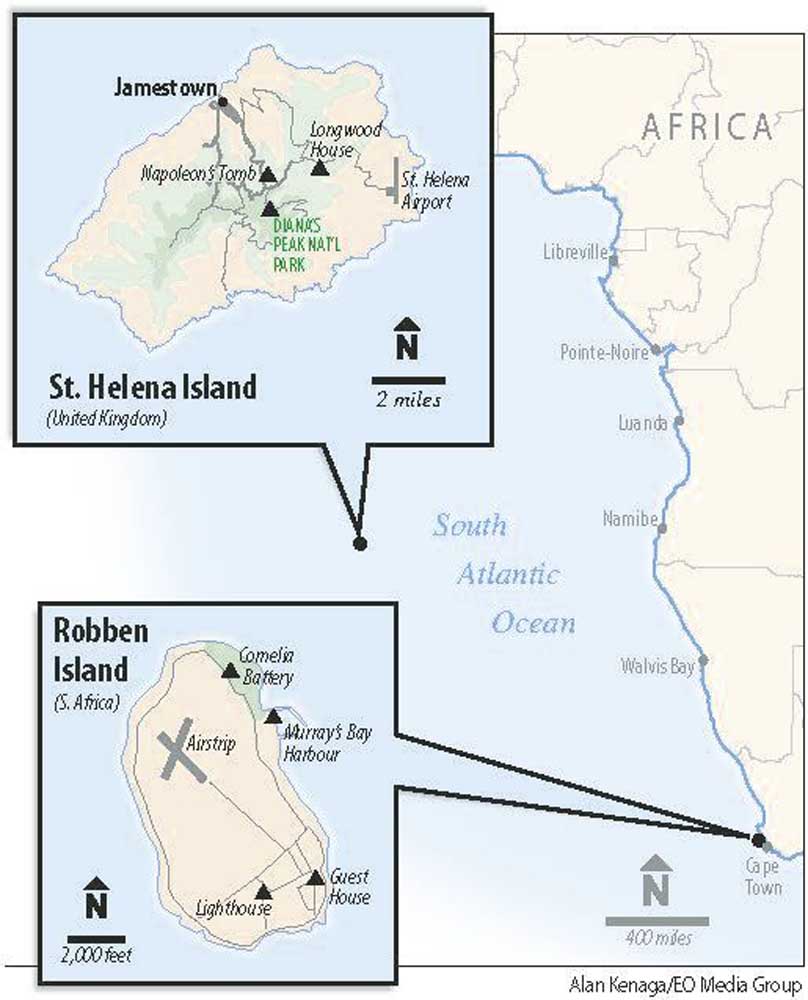

- Maps of St. Helena Island and Robben Island.

On a January trip to South Africa and the South Atlantic, my wife and I saw two of the world’s most storied places of captivity: Robben Island off Cape Town, and the island of St. Helena.

Trending

Nelson Mandela was imprisoned for 18 years on Robben Island. Napoleon was the captive of St. Helena for six years and entombed there for another 19.

Viewed from Capetown, Robben Island is an indistinct land mass — two miles of flatness lacking sharp contours. In addition to a place of imprisonment, the island was a leper colony, beginning in the late 1800s. Some 1,000 persons are buried in the island’s leper cemetery.

Robben Island contains two prison sites: one for conventional criminals, another for political prisoners during the Apartheid era. Apartheid was the South African system (1948-1986) that systematically separated the non-white population and inflicted an onerous code in which blacks were forced to carry passes. Dissidents like Nelson Mandela were sentenced to Robben Island. The prison in which Mandela and hundreds of others were held is not large.

Trending

The startling aspect of our prison tour was the guide. He was a former political prisoner. Following a brief introduction, the man took our group of about 30 to the dormitory where he had been confined. It contained eight bunk beds and a common space.

We sat on benches while he spoke to us for about 30 minutes. He told us of young political prisoners who were hanged on Robben Island. He described the distinction between detention and imprisonment. The defining aspect of detention was torture. That is why, he said, imprisonment was preferable.

From the dormitory he walked us into a large courtyard, in which prisoners sat on the ground and broke rocks. Reentering the building, midway down a hallway, we saw Mandela’s small cell.

Prior to ending the tour, our guide was asked about his feelings in coming back to that prison. “We bear no grudge,” he said. That exhortation and everything he had shown us was the equivalent of a dramatic and poignant sermon on that sunny Sunday morning.

‘Nowhere’

People travel to St. Helena for one reason: Napoleon. My grandmother inspired me to make the trip. She took this sea voyage, likely on a British supply ship, in the 1950s or 1960s. During my childhood visits to her room, I observed the small watercolor of a corpulent Napoleon that she had purchased on St. Helena.

In the early morning hours of a Sunday, it was thrilling to catch the first glimpse of St. Helena. The island is the top of a volcano. It juts from the ocean like an immense rock fortification.

Almost halfway between West Africa and Brazil, this speck in the ocean is commonly referred to as “nowhere.” Following Napoleon’s escape from his first exile, on Elbe, and the subsequent carnage of the Battle of Waterloo, St. Helena’s extreme remoteness speaks to Britain’s eagerness to put Napoleon away, for good.

The island is a British possession with a governor. The French are represented by a consul. The Tricolor flies at two French properties: Napoleon’s house called Longwood and Napoleon’s first tomb.

From my reading about St. Helena, I had expected heavy wind on the plain where Longwood resides. Wind and the drafty home sometimes drove Napoleon to distraction. On the day of our visit, however, the atmosphere was placid. Without constant refurbishing, Longwood would deteriorate from the weather and termites. The French government invested. One sees Napoleon’s small bedroom, the bathroom with its deep metal tub, the room in which he died, the dining room that an abundance of candles made oppressively hot as Napoleon’s court stood about in full dress. An excellent rendition of the atmospherics of Longwood is Jean-Paul Kauffmann’s book “The Black Room at Longwood.”

The pathway to Napoleon’s tomb is sufficiently wide for 14 grenadiers to have carried a coffin and placed it on a horse-drawn carriage. There was no name on top of the tomb, because the British and the French could not agree on the wording. During the period of Napoleon’s presence inside the tomb, visitors carved their initials on the top. Today the visitor is kept at a distance.

We saw the residence to which Napoleon and his party rode for a surprise picnic lunch two weeks prior to his death. St. Helena’s fortress exterior hides a lush, green interior. It is said to have multiple ecosystems. And it has a bird that appears nowhere else.