Place names are reminders of Cannon Beach’s first citizens

Published 6:07 am Thursday, October 19, 2017

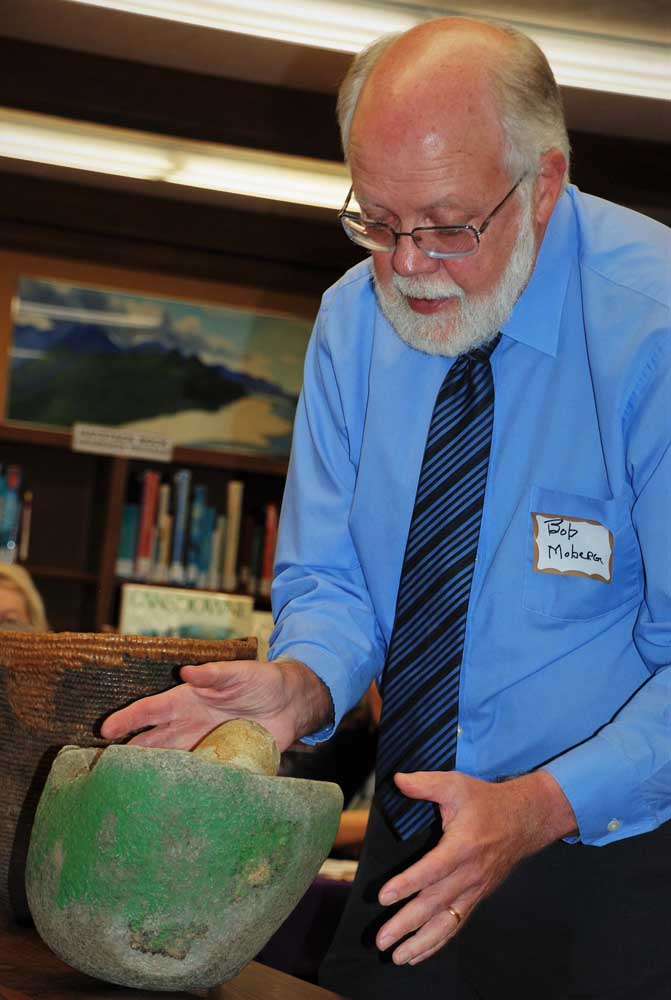

- Retired Seaside attorney and municipal judge Robert Moberg displays a stone pestle and mortar found in Columbia River basin. Moberg, who is 1/16th Chinook, believes the mortar and pestle was used by Indians to grind food. He displayed it during a lecture he gave at the Cannon Beach Library.

How tribes conveyed history

By Nancy McCarthy

For the Cannon Beach Gazette

Cannon Beach hasn’t always been a tourist Mecca or even an arts colony.

Until the mid-19th century, Cannon Beach, as well as the rest of the North Coast, was home to the Clatsop and Chinook tribes.

“The Chinook and Clatsop Indians were the first residents of Cannon Beach. They were here probably for thousands of years. For the most part, these proud people are gone,” Robert Moberg, retired Seaside attorney and municipal court judge, told those attending the Cannon Beach Library membership meeting Oct. 4. The meeting also was one of the events planned this year to celebrate the library’s 90th anniversary.

Moberg, who is 1/16th Chinook, is a descendant of Chinook Chief Comcomly.

“It’s hard to imagine what Cannon Beach was like 150 years ago,” Moberg said. “In the 1850s, there were very few Caucasian people here; one book indicates there were only four Caucasians in Astoria in 1850.”

Native Americans, however, “would have been numbered in the tens of thousands,” having originally traveled over a land bridge, he added. “Clatsops and Chinooks were probably composed of many nationalities that arrived at the mouth of the Columbia River and the Chinooks, who lived mostly north of the Columbia River, were part of a “vast trading empire,” Moberg said.

While the tribes’ oral traditions extend back hundreds of years, their written history begins with the journals of Merriweather Lewis and Lewis Clark, who explored the local area in 1805. The explorers considered the tribes “quite admirable,” Moberg said.

“They described them as ‘mild with good sense, loquacious and inquisitive, king traders that held their own with the expedition.”

Their major occupation, Moberg added was “trade, not war, although they were pretty good at war.”

“Indians in this area had a much greater standard of living than most of those in most of the United States,” Moberg said. Their longhouses, made out of cedar planks, were dug five feet into the ground. Sometimes, more than one family lived in a longhouse.”

Slaves were kept, he added, but they often were treated like members of the family, staying in the same longhouse.

“They were treated fairly well, except, on occasion, if the master died, they would kill the slave and bury it with the master.”

A good slave was worth “as much as a horse or 10 to 12 blankets,” Moberg said.

Celebrated for their skill in making canoes, the local tribes would travel up the Neawanna River, down the Neacoxie, to Sunset, Long and Smith lakes in Warrenton, portage to the Skippanon River and on to the Columbia River and would “go pretty much with ease several days up to The Dalles and Celilo Falls,” Moberg said.

“Considering the clumsy tools they had to construct the canoes, they were marvelous,” he added.

Lewis and Clark wrote that they were “amazed at the ease with which they navigated the stormy waters.”

When the local Indians died, they weren’t buried, but placed on scaffolding with all of the deceased’s possessions to take with them to the hereafter. “In 1852, there was a report that there were bodies in scaffolding from (what is now) Avenue A to Avenue U in Seaside” because of a smallpox epidemic,” Moberg said.

Cecust “Elizabeth” Lattie and her son were the only two Native Americans in the country to claim and receive property under the Land Donation Act of 1850, according to Moberg. In 1852, Elizabeth, a Clatsop, claimed the land between the current Avenues A and U, and her son, William Lattie, claimed property from Avenue U to the Cove. A portion of William’s property became the site for Benjamin Holladay’s Seaside Hotel, which signaled the beginning of Seaside as a resort community.

The federal government doesn’t recognize the Chinooks and Clatsops as tribes because there were not enough members to constitute a tribe, Moberg said.

“Why? Because white men’s diseases had wiped out 90 to 95 percent of the people,” he said. “They were dispersed and not recognized as a tribe. We’re not here to lay blame but to remember the first citizens of Cannon Beach who all but perished under the civilization and way of life of the white man.

“These were people who welcomed the stranger, migrants and should be remembered with the words Ecola, Neacoxie, Necanicum, Skipanon … and Clatsop. These names are indelibly stamped on Cannon Beach and all of Clatsop County so that we will not forget those first citizens of Cannon Beach.”