Organic farming is at a crossroads

Published 5:06 am Tuesday, February 21, 2017

- Organic farming is at a crossroads

At this point, maybe organic producers and processors should just declare victory.

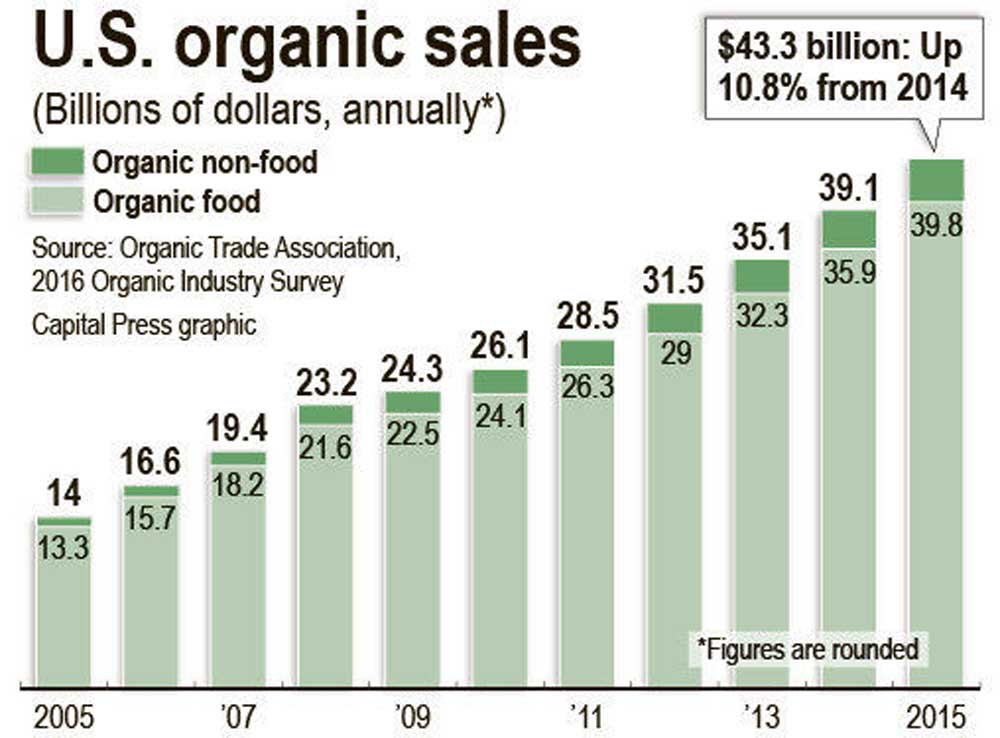

They’ve won, haven’t they? Sales of organic products show double-digit growth year after year. Consumers increasingly associate organics with safer food and better nutrition, health, soil and plants, not to mention more humane treatment of livestock and better conditions for farmworkers.

That little green U.S. Department of Agriculture Organic symbol on a package says this costs more because it’s special. And it’s all delivered by a chemical-free small farm worked by a smiling couple and their beautiful brood of happy children.

Right?

Well, sure, to a certain extent.

But within the organic community, some worry the movement — and that’s how many see it, as a movement — will lose its soul as “Big Ag” takes over organic production and snaps up small organic processors.

“If we continue to mainstream, is there anything left of what was organic, or do we just become product manufacturers?” asked Oregon organic pioneer David Lively.

As the Costcos, Wal-Marts and Krogers of the world continue to enter the organic market, “Are they really concerned with what we’re doing, or is it a marketing opportunity?” Lively said.

There are other issues out there, of course. Producers disagree over the proposed organic checkoff, for example, and whether a “transitioning to organic” label is proper for growers who are headed that way but aren’t yet certified.

And although organic product sales grew 11 percent to reach $43.3 billion in 2015, and have undoubtedly topped that in the interim, the number of organic farmers has actually dropped. Organic products now make up nearly 5 percent of U.S. food sales, but organic acreage is less than 1 percent of U.S. cropland, according to the Organic Trade Association.

It appears millennials, the 18 to 34 age group, account for more than half of organic purchases. That means a lot of people still aren’t convinced they should pay more for something that often looks and tastes the same as conventional vegetables, fruit, grains and meat.

“It would be shortsighted if we strive only to fill the shopping baskets of millennials and be happy at that,” warned Drew Katz, who coordinates farm transitions for Oregon Tilth, an organic certification group.

But it’s creeping bigness that seemed to bother many of the 1,100 growers, processors and activists who attended the three-day Organicology conference and trade show in Portland earlier this month. One of the panel discussions was even titled, “Challenging the Empire: Forming a Rebel Alliance.”

The rebels might have reason to worry. Phil Howard, a Michigan State University professor, has tracked the acquisitions of organic operations by the biggest “Deathstars” in America’s food system.

Organic activists can recite some of them from memory: General Mills now owns Annie’s Homegrown and seven other organic brands. Coca-Cola owns Odwalla and Pepsi owns Naked Juice. Kellogg owns Morning Star and Kashi, plus two other brands. J.M. Smucker bought R.W. Knudsen, Millstone, Santa Cruz Organic and Enray. Food giants Foster Farms, Tyson, Hormel and Nestle also own several organic brands.

Costco helped another company buy 1,200 acres in Mexico, and will use it to supply its membership warehouse stores with organic products.

Wal-Mart barged into organics 10 years ago, vowing it would bring cheaper organic food to the masses. Critics soon alleged Wal-Mart’s organics were coming from factory farms and from China, with its checkered food safety and regulatory history.

Food writer Michael Pollan said the company’s low-price promise “virtually guarantees that Wal-Mart’s version of cheap, industrialized organic food will not be sustainable in any meaningful sense of the word.”

Meanwhile, the Washington Post reported Feb. 9 that mass-market retailers now account for 53 percent of organic sales and that Whole Foods, one of the pioneering organic chains, is closing nine smaller, older stores and only opening six.

Brian Baker, a Eugene organic consultant who moderated the “Empire” panel discussion at Organicology, said it’s not the soul of the industry he’s worried about, but rather its integrity.

“My point was that corporations that enter the organic sector through the acquisition of organic enterprises behave differently from operations that have gone through the hard work of transition or have practiced organic production and handling from the beginning,” he said in an email.

Conventional food corporations generally don’t understand what it takes to become organic, Baker said. They know the organic sector is growing and sells at a premium price, but lack organic production experience and don’t have a first-hand understanding of organic standards.

“The concern is particularly acute if the corporations behave as if the rules that applied to the companies they acquired do not apply to them,” Baker said.

While some attending Organicology hold tight to the “purity” of the movement’s hippie, back-to-the-land origin, as one observer described it, others are seeking a better balance.

The Cornucopia Institute, based in Wisconsin, has served as a watchdog on organic issues, battling the USDA, the Organic Trade Association and corporations such as Wal-Mart when it believes the spirit or letter of organic guidelines are violated.

But Mark Kastel, co-director and senior farm policy analyst, said Cornucopia’s message is more nuanced than “big is bad.”

“The issues are not corporate scale, they are about corporate ethics,” he said. “This is a values-based industry. It’s grown to $43 billion (in sales) because consumers wanted an alternative to standard practices in growing agricultural commodities and in processing, too.

“If you respect the wishes and values of consumers, there is money to be made here and profit to made here at the farm gate and in the boardroom.”

Gina Colfer, a key account manager with Wilbur-Ellis in Salinas, California, is on the frontlines as a big, conventional ag company transitions itself to join the organic marketplace.

Colfer, with experience in agronomy, pest control and food safety, was working for Earthbound Farm, which itself had grown from a small startup farm to a national organic producer, when Wilbur-Ellis came calling.

Wilbur-Ellis has been around nearly 100 years, and provides fertilizers, pesticides, seed and crop monitoring services to farmers in the West and into the central states. Growers began asking Wilbur-Ellis reps about organics, and the company decided it didn’t want to get left behind, Colfer said.

“We didn’t want to tell our growers we didn’t know,” she said.

She was brought on board to help growers answer those questions and become organic producers. She offers options and advice on methods, employing what she calls a whole systems approach.

“We want to help these growers learn that you’re not going to spray your way out of a problem,” she said. “You have to address the soil, and build soil health first and foremost.”

Other things follow, like improving pollinator habitat by planting native, perennial flowering plants and faster growing annuals in strategic areas.

Growers who follow a whole systems approach, no matter their size, advance organics, she said.

“For me, I look at the greater good,” Colfer said. “If we can keep more synthetic pesticides and fertilizers out of the environment, it’s a win-win for everyone. Building soil health, I think, crosses over all lines.”

And having organic products in larger marketplaces, she said, opens opportunities for consumers who might not otherwise be able to buy organics.

“We’re all in this together,” Colfer said. “People, planet and profit. All three of those have to be in place for it to be sustainable.”

Online

http://bit.ly/2m4A0D6