Conscientious courage

Published 6:05 am Saturday, September 24, 2016

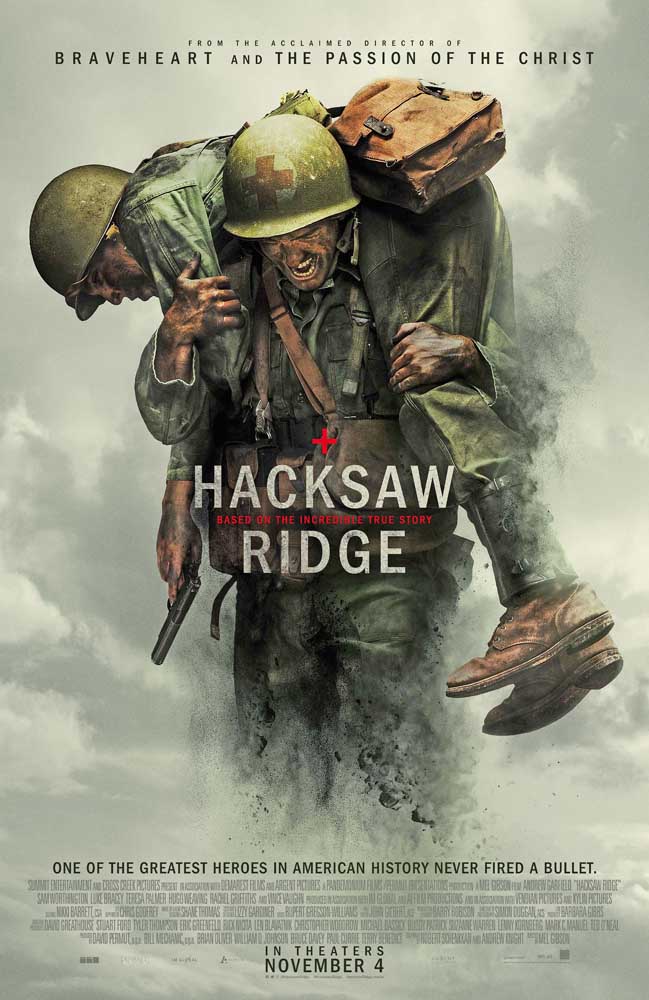

- A movie poster for the upcoming film “Hacksaw Ridge,” by Mel Gibson, which is set for nationwide release Nov. 4.

Desmond Thomas Doss was working at a naval shipyard when the U.S. entered World War II. As a ship joiner and a practicing Seventh Day Adventist, he was offered a deferment, but instead chose to join the war effort voluntarily, enlisting in the Army soon after hostilities began.

Trending

Doss later explained his decision, saying, “While I believe in the commandment ‘Thou shalt not kill,’ and that bearing arms is a sin against God, my belief in freedom is as great as that of anyone else, and I had to help those boys who were fighting for it.”

Rather than refer to himself as a conscientious objector, Doss — whose son, Desmond Doss Jr., lives in Ilwaco, Washington — preferred his own term, “conscientious cooperator,” and asked to be assigned to medical duty where he could save lives, not take them. He became a company aid man, or medic, in the 307th Infantry Regiment, 77th Infantry Division.

Without ever picking up a weapon in war, Doss’ heroics through some of the fiercest fighting in the Pacific would earn him the Medal of Honor. He was the first conscientious objector to receive such recognition, and now, more than 70 years after he has been credited with saving upwards of 75 men from near certain death, the story of Doss’ moral and physical courage is being told on the big screen, Hollywood style. “Hacksaw Ridge,” directed by Mel Gibson, opens in theaters in November nationwide.

Trending

Born in Lynchburg to a family of strict Seventh Day Adventists, Doss’ elevation from a simple son of the South to a highly decorated war hero did not come easy. Gibson’s film appears to chronicle the difficult trajectory of Doss’ life and his ultimate triumph.

Private Doss was said to be mocked for kneeling next to his bunk to pray and often accused of shirking his duty for refusing to handle a weapon. His early days in the army were fraught with verbal and physical abuse as Doss refused to work on Saturday, the Sabbath, according to his religious beliefs. At one point, an officer tried to have Doss discharged on grounds of mental illness. All the while, Doss refused to bend.

If his fellow soldiers were confused about Doss, it was ultimately in battle that he would show them his true character.

In spring of 1945, Doss accompanied his fellow troops in a dramatic push to take a 400-foot-high strategic ridge, the Maeda Escarpment, known later to Army infantrymen as Hacksaw Ridge. As thousands of U.S. soldiers swarmed the high point, the Japanese launched a blinding counterattack. Many of the Americans retreated, but hundreds were left wounded and stranded atop the ridge.

Private Doss remained and quickly began fulfilling what he saw as his duties to both his fellow soldiers and to God. According to his Medal of Honor citation, Doss “refused to seek cover and remained in the fire-swept area with the many stricken, carrying them one by one to the edge of the escarpment and there lowering them on a rope-supported litter down the face of a cliff to friendly hands.”

He did it over and over. And that was just one day.

For weeks on end, Private Doss returned to the thick of battle, and continued to save lives. Under heavy machine gun fire, he rescued a wounded soldier 200 yards in front of American lines. Days later, according to a Library of Virginia biography and historical notes, Doss made four trips under fire to save four soldiers wounded within 25 feet of a heavily defended cave. He was credited with carrying another wounded soldier to safety hundreds of yards under heavy shelling and small arms fire. Later, after saving dozens more lives, a grenade blast seriously injured Doss while he was attending to wounded soldiers. Rather than calling another medic away from the battle, Doss dressed his own mangled legs and kept working. Then, hours later, while Doss was being carried from the scene, he leapt from his stretcher and directed other medics to help a more critically wounded soldier. In the chaos that followed, Doss was hit by enemy fire. With his arm fractured, he used a rifle stock as a splint — perhaps the only time he touched a weapon — and then crawled 300 yards to an aid station.

Doss was the first conscientious objector to win the Medal of Honor. He was promoted to corporal and presented the award by President Harry Truman along with 14 other men at the White House in 1945. He rode a bus back to Lynchburg a few weeks later, and was greeted with a massive parade in his honor.

The war and its wounds took a toll on Doss and he spent six years in and out of veteran’s hospitals. While recovering, he contracted tuberculosis and had a lung and several ribs removed. Later, he suddenly lost his hearing. He was never again able to work a physically demanding job, but continued to stay very active in the Seventh Day Adventist church and he kept up a busy schedule of speaking engagements and events.

Despite whatever recognition he received for his heroic action in war, Doss — who died in 2004 at 86 — was always quick to divert the credit.

“From a human standpoint, I shouldn’t be here to tell the story,” Doss said in a 1998 interview with the Richmond Times-Dispatch. “All the glory goes to God. No telling how many times the Lord has spared my life.”