The ‘ugly’ alternative

Published 6:02 am Tuesday, September 6, 2016

- The ‘ugly’ alternative

WENATCHEE, Wash. — Sometimes, farming can get ugly.

When hail damages tree fruit and field crops, or when produce just doesn’t meet the high visual standards of grocers, it often goes into secondary channels or is rejected.

For example, weather-damaged apples are normally made into juice, and the unlucky growers receive only a fraction of their usual value.

But as this season’s harvest continues, Columbia Marketing International has come up with a more lucrative option for the hail-nicked fruit from two of its orchards. CMI aims to capitalize on a growing food trend, marketing discounted, superficially blemished fruit through fresh channels as “ugly” produce, providing environmentally conscious consumers a means of taking action against food waste.

“It’s a nice way for us to potentially help growers who for whatever reason — hailstorm, windstorm or whatever — are facing a catastrophic loss,” Steve Lutz, CMI vice president of marketing, said. “It’s a fabulous alternative.”

CMI — the marketing arm of four packing sheds in Wenatchee, Quincy and Yakima — launched its I’m Perfect brand of apples — a play on the word “imperfect” — earlier this year, featuring fruit that isn’t aesthetically pleasing but still has acceptable quality to eat.

The ugly produce movement has gained momentum nationwide for several commodities, aligning the interests of farmers, who would like fresh market options for more of their production, and food activists, who want to reduce food waste in an effort to feed more people.

Facing mounting consumer pressure, the world’s largest grocer, Bentonville, Arkansas-based Walmart, recently agreed to offer I’m Perfect fruit at 300 of its Florida stores as part of a corporate ugly produce pilot program.

Lutz said I’m Perfect apples will likely sell for roughly half the cost of unblemished fruit, but the return will still be far superior to making juice, which pays about $50 per ton.

By comparison, the August return to first handlers at Wenatchee was $19 to $22 for a 40-pound box of the largest size of top-quality red delicious apples, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. A ton of those same apples, blemished and marketed as “ugly,” could still fetch up to $550, assuming half the usual rate of return.

Lutz emphasized I’m Perfect will fill a small and seasonal niche, offered mainly around harvest time, and CMI will have to be “very strategic in how we use the program” to reach new consumers rather than having existing buyers “shift down.”

Walmart officials learned of I’m Perfect when they were reviewing programs at CMI earlier this year and “got very excited about it,” Lutz said.

About a month ago, Walmart bought a small quantity of scuffed 2015 Granny Smith apples and quickly sold out. He anticipates one of this season’s hail-damaged orchards will yield 30,000 boxes of I’m Perfect fruit.

In a July blog posting, Walmart officials also referred to their new Spuglies brand of ugly potatoes — weather-damaged russets raised in Texas — and the “Wonky” vegetable program at Walmart’s Great Britain outlet, Asda.

“What excites me the most about the launch of these I’m Perfect apples is that it is a result of working with our suppliers to build the infrastructure and processes that create a new home for perfectly imperfect produce,” Shawn Baldwin, Walmart’s senior vice president of global food sourcing, produce and floral, said in the blog. “Because ugly produce can occur unexpectedly in any growing season or crop, we want to have the systems in place to offer this type of produce whenever it may occur.”

Jordan Figueiredo is on a mission. His goal is to feed more people with the ugly food that many grocers reject.

In his free time, Figueiredo, of Castro Valley, California, a suburb of San Francisco, is an anti-food waste crusader with 140,000 social media followers, blogging about strategies such as state-funding to cover farmers’ labor costs to pick and pack ugly produce for food banks.

In 2014, Figueiredo organized Feeding the 5,000 in Oakland — a free public meal made with food that would have otherwise gone to waste.

“We gave away 9,000 pounds of produce, stuff that was rejected by grocers,” Figueiredo said. “Since then, I’ve been hooked on ugly food.”

Figueiredo started online petitions encouraging Whole Foods, of Austin, Texas, and Walmart to test ugly food. Both companies subsequently announced pilot projects.

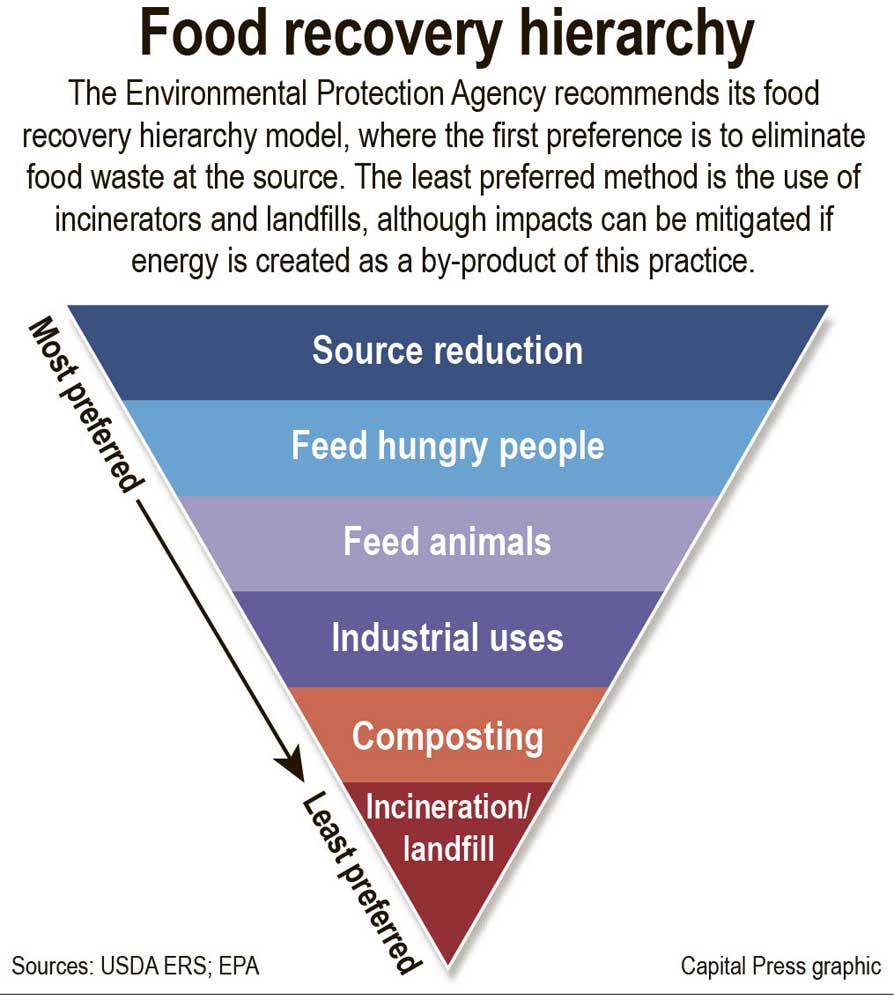

Figueiredo points to USDA statistics as evidence of the scope of the food waste problem. The agency estimates 30 to 40 percent of food in the U.S. is wasted. Wasted food is also the largest category of garbage dumped in landfills, according to USDA.

Yet the World Food Program estimates 795 million people in the world are undernourished, and 45 percent of the deaths of children under age 5 result from malnutrition. Even in the U.S., 14 percent of households were described as “food insecure” due to poor access to adequate nutrition in 2014, according to USDA. Of the estimated 48.1 million food insecure Americans, 15.3 million were children.

“It’s a social outrage that so many people are food insecure and we’re throwing away so much good food,” Figueiredo said.

But lately, he’s also noticed progress. In September, USDA and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency announced a national goal of working with state and local governments to reduce food waste in half by 2030.

“Almost 90 percent of Americans aren’t eating five recommended servings of fruits and vegetables per day,” Figueiredo said. “You can get cheaper produce that’s still fresh and good to folks who normally wouldn’t be able to buy it.”

Blackfoot, Idaho, produce farmer Richard Johnson has found the public is far more accepting of ugly produce if it comes from a familiar, local source. At farmers’ markets, Johnson mixes ugly produce with his top-quality fruits and vegetables and offers no discount.

Most of it sells, and he donates anything left over to the local food bank.

Johnson said when grocers buy produce, they may turn away as much as 40 percent of a farmer’s production for purely cosmetic reasons.

“Too much of our food we don’t use to its full potential because of some standards that say, ‘This is Grade-A quality,’” Johnson said.

Some ugly food sellers go straight where they are needed most.

In Cleveland, wholesale produce suppliers Ashley and Andy Weingart have contracted with a courier service to deliver ugly fruits and vegetables to households in a designated food desert. They mark down the produce by about 40 percent, but they emphasize they couldn’t sell it otherwise, and the program fills a community service, providing fresh produce to low-income households.

The ugly food deliveries started in May and now reach about two dozen customers. Andy Weingart anticipates working with farmers to harvest more of their ugly crops as demand grows.

“The idea is to reach out to some growers so instead of plowing those (ugly) items in the field, to convince them there is still demand for those items,” Andy Weingart said. “It’s a shame so much of our business has to be No. 1 quality, or top-shelf.”