Long DNA journey leads to the Pyrenees Mountains

Published 8:00 pm Thursday, July 9, 2015

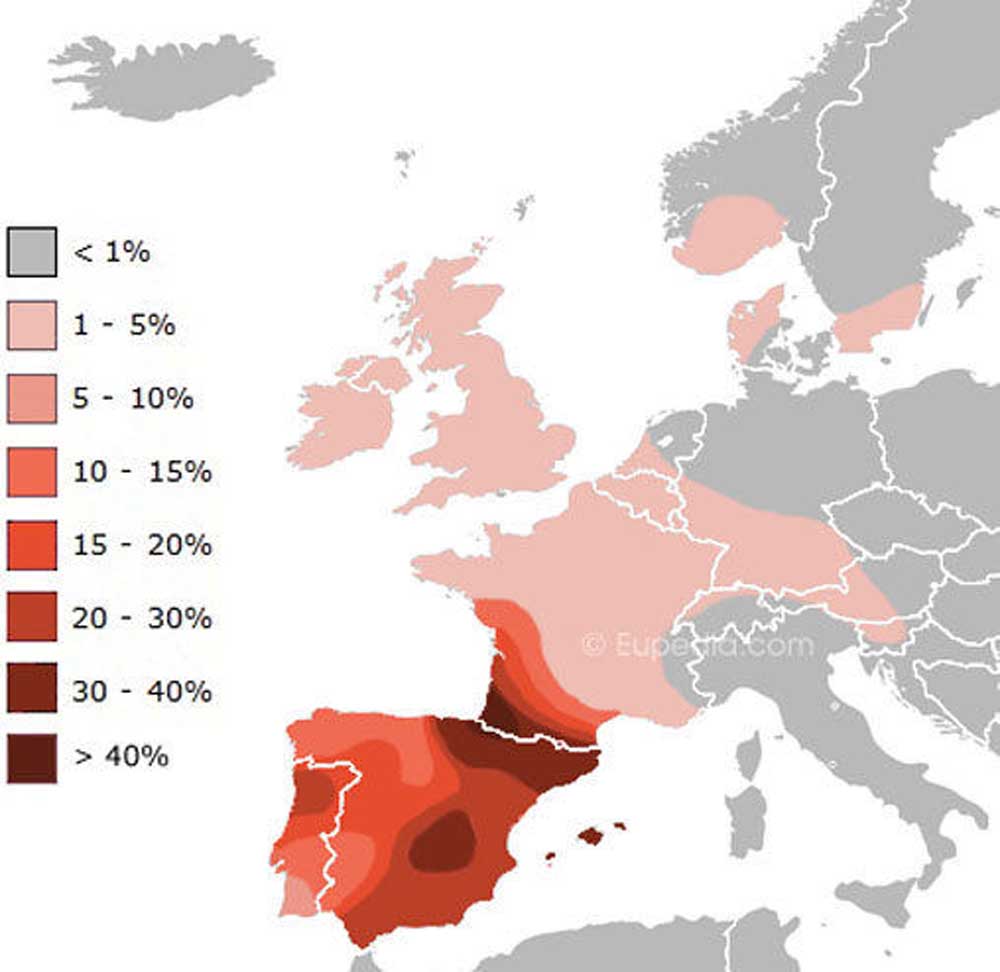

- A map from the Eupedia website identifies the homelands of men with the genetic marker DF27. It reaches its highest concentration in Basque Country in northern Spain and Southwest France. Matt Winters is DF27.

Solitary old men in berets, taciturn and self-sufficient as black basalt poking out of the thin desert soil. They are still honored back in their homeland.

“The oldest brother, they got the land. The younger ones, they went to North Dakota, Montana, Wyoming,” our Basque host told us last month. Freshly shorn sheep dot the sheer, exuberantly green hillsides of Basque Country in Spain and far southwestern France. Sheep remained the tribal business America, too – with those immigrant little brothers spending months at a time alone in their canvas-sided sheepwagons out on the soul-stretching emptiness of America’s vast high prairie.

Like the unfathomable inhabitants of far-flung islands floating in an ocean of close-cropped grass and sagebrush, they were perfectly accustomed to being left alone. But they also delighted in visiting by their campfires, sharing boiled black coffee in chipped enameled metal cups. Just writing these words brings back a strong whiff of sage smoke.

In a 2005 story in the Casper Star-Tribune, my old newspaper, Cat Urbigkit wrote of the enduring “transhumance” method of raising sheep, a practice that started in the Pyrenees Mountains — home to the Basques and Gascons. It is an artfully calculated migration between low country and alpine meadows, pursuing the best new grass while avoiding killing winter snows.

“Basques began moving to Wyoming in the early 1900s to herd sheep. Many of their descendants are still here. For example, sheep herds belonging to one Basque family, the Arambels, migrate to high country along the Continental Divide in the Wind River Mountains in the summer, then travel several hundred miles through western Wyoming to winter on the desert south of Interstate 80 near the Colorado border,” Urbigkit observed.

Within Basque Country, only the size of Maryland, this seasonal cycle is compressed within only a few miles but an elevation change of as much as 6,000 or 8,000 feet.

With amazing continuity, families have made their homes in these mountains and valleys for thousands of years. In amateur genetics circles, we revere the ice age refugia — the Steppes of southern Eurasia, the upper Black Sea coast, the Italian Peninsula — places that harbored our European ancestors when the glaciers advanced southward, swallowing lands and making much else nearly uninhabitable.

Honeycombed with limestone caves, the Pyrenees formed the northern boundary of the relatively warm Iberian refuge. If your heritage is any kind of Western European, your direct distant relations lived and worshiped in these caves. They are our old family homes, as much as the little wooden house you grew up in.

On June 22, my wife and I threaded our way up along wildly twisting mountain roads to the Grottes de Sare, a Cyclopean-sized cave system. Some say it cuts all the way through to Spain, making it a handy avenue and hiding hole for the village of Sare’s former main business, smuggling or “night work.”

There’s no danger of confusing it for a snug and comforting Hobbit hole, but the Sare cave does offer obvious advantages. It is fairly dry but has a pure (except for the droppings of a dozen different bat species) little stream running through it. It opens onto a fertile and defensible forest glen. Its crooked nooks and soaring crannies could probably hide hundreds of people and their herds from blizzards or war parties — though its actual population probably was never more than an extended family at any one time.

I, the only English speaker, trailed the end of a small tour group that meandered along a path illuminated by flickering motion sensor-activated lights. Occasionally, I peered backward into darkness seeking that frisson of recognition, a DNA-level feeling that my people were here before. The slow, dripping silence of eons answered.

Though I didn’t manage to spot any caveman ghosts, my wife and I did love meeting a great many Basques in our temporarily adopted town of Saint-Jean-de-Luz, which celebrated its patron saint’s day on June 21 with happy community parades, bands and parties that Sunday and several days leading up to it.

Like the African-American descendants of slaves whose only hope of identifying a long-lost ancestral homeland is genetic testing, 10 years ago I turned to DNA to gain a sense of where my distant Winter forefathers started out. Eventually, traditional genealogy led us back to early colonial Massachusetts and beyond that to London. But genetics may now carry our family story even farther, to the wine-growing region of Aquitaine/Bordeaux in what is now Southwest France but which was part of England from 1154 to 1453. Wine merchants from the region, called vintners, became economically entrenched in London. Four vintners served as mayor in the reign of Edward II. In England, the occupational surname Vintner morphed into Winter.

Aquitaine, the Pyrenees and Spain are thick with my distant cousins including the Basques — men defined by a genetic marker called DF27. All of us who have this marker are descended from a man who lived in the region about 4,600 years ago, part of a Neolithic immigrant group that arrived with new farming and metallurgy techniques.

None of this means I’m specifically a Basque — Basque men are DF27, but so are a great many Spaniards, Gascons, Catalonians and Portuguese. But Basque Country has the strongest concentration of us. My trip was a kind of valedictory homecoming, a quiet way of paying tribute to dozens of generations of younger sons whose migrations, in my case, culminated at the mouth of the Columbia River.

Wearing my red and black jacket, the Basque colors, I sat in Saint Jean’s plaza listening as a pop singer belted out in Basque one of my favorite songs, Curtis Mayfield’s “People get ready, there’s a train a-coming, you don’t need no baggage, you just get on board.”

After a long, long journey, one of us came home.

—MSW

Matt Winters lives in Ilwaco, Wash., with his wife and daughter.

My trip was a kind of valedictory homecoming, a quiet way of paying tribute to dozens of generations of younger sons