Son’s rare malady spurs statewide awareness

Published 5:04 am Thursday, July 2, 2015

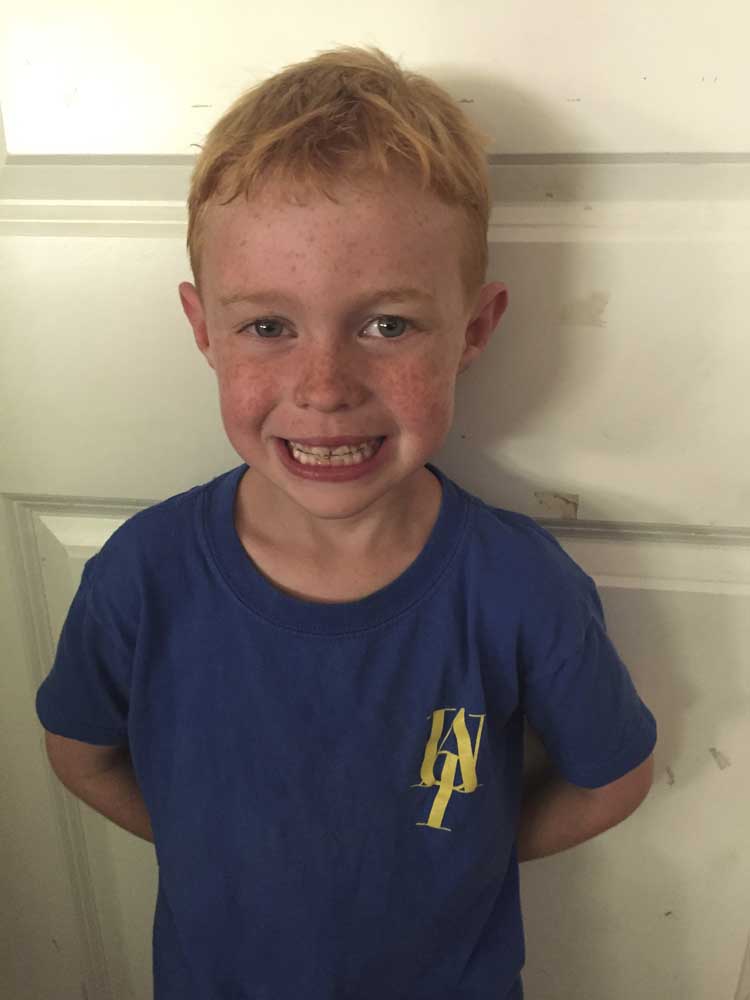

- Tristan Norgaard has congenital adrenal hyperplasia, or adrenal insufficiency, a disease that affects 1in every 10,000 to 18,000 children across the country.

An Astoria mother’s campaign to raise awareness about her son’s rare medical condition went statewide last month.

The Oregon Legislature passed two bills this session supporting those with adrenal insufficiency, a genetic condition that occurs when the body is unable to produce enough cortisol, the stress hormone vital to life.

Kirsten Norgaard’s 7-year-old son, Tristan Norgaard, was diagnosed with adrenal insufficiency one week after he was born. Since then, she educated herself and has advocated for more awareness. The disease impacts 1 in every 10,000 to 18,000 children.

Motivated by her experience, Kirsten Norgaard helped form the nonprofit Adrenal Insufficiency United, or AIU, with Eugene resident Jennifer Knapp, whom she met through a Facebook group.

“What we are doing is trying to save lives and trying to educate people about his condition,” Norgaard said. “If we don’t educate, nothing will change.”

Before pursuing state legislation, Norgaard started her push for awareness locally in Clatsop County. She recalls about three years ago she happened to start a conversation with local paramedics, while on shift at her job at Wet Dog Cafe in Astoria.

She asked the paramedics if they carried the specific medicine, Solu-Cortef, necessary for people with adrenal insufficiency. Without the medication, the condition can be fatal.

The paramedics said they did not carry the medicine.

Norgaard helped write protocol for Medix, comparing Solu-Cortef to insulin needed by diabetics. The medicine is now available by Medix and at Columbia Memorial Hospital.

“That is part of our daily struggle. If we go somewhere that is not Clatsop County, where we have protocol, is he going to be safe? The answer is, ‘no,’” Kirsten Norgaard said.

Changing the law

The two bills that passed this session are Senate Bill 874 — requiring the Oregon Health Authority to train healthcare professionals about adrenal insufficiency — and Senate Bill 875 — allowing trained school personnel to administer medication to students.

Both bills go into effect in January.

State Rep. Alissa Keny-Guyer, D-Portland, offered her input during the final reading of SB 874.

“The most urgent need in the adrenal insufficiency community is for protocols to treat adrenal insufficiency in the prehospital and emergency department settings,” Keny-Guyer said. “Many other states and cities have created and used protocols to save lives. We need the same in Oregon.”

Norgaard credits Knapp, who took time away from her work to be in Salem full-time during the legislative session, and state Sen. Betsy Johnson, D-Scappoose, who supported the bills from Day 1.

For the first hearings in Salem, Norgaard brought her son and 9-year-old daughter, Faith Norgaard. The group personally handed out cupcakes to the lawmakers’ offices. The cupcakes were in honor of a girl named Annie who died after being misdiagnosed when she had adrenal insufficiency. The girl’s favorite thing to do was bake cupcakes with her mom.

“That little personal story opened so many doors,” Kirsten Norgaard said.

Spending time in the state capital was an eye-opening experience for the Norgaards. Senate Bill 874 had opposition from lobbyists who claimed the medical community already knew about the condition.

Norgaard said she had a hard time explaining lobbyists to her two children.

“My little girl wondered how anyone would want her brother to die,” she said. “How can you explain that?”

Staying safe

Norgaard admits she was terrified when her son started kindergarten. With the school nurse only available once a week and school staff not trained in administering the medication, she was worried what might happen if her son had a problem.

“Whoever he is with, I have to make sure he is safe,” she said.

A couple of weeks ago, Tristan Norgaard had an incident that proved the importance of having adrenal insufficiency medication readily available. He was hit in the mouth with a metal baseball bat before a T-ball game. For other people who get smacked in the face with a bat, their cortisol levels start pumping at 10 times the normal level. For Tristan, his cortisol does not pump at all.

“If I wasn’t there at that game, he would have gone into shock and within 30 minutes he could have been dead,” Kirsten Norgaard said.

With awareness increasing across the state, Norgaard does not worry as much anymore.

She recently met a local man who said he was just diagnosed with adrenal insufficiency at Columbia Memorial Hospital.

“That is because of Tristan and the protocol we have at CMH,” Norgaard said. “Because they know to find symptoms, because that is part of the protocol, they were able to save him.”