Editor’s Notebook Classic sci-fi novel foretold avant-garde quantum theory

Published 7:00 pm Thursday, December 4, 2014

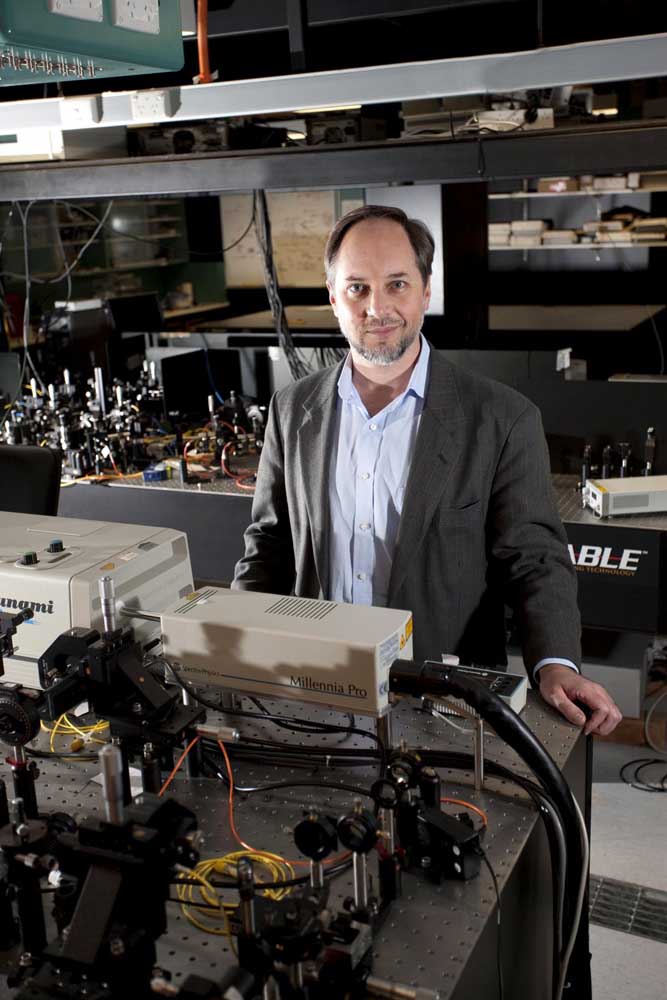

- This is Professor Howard Wiseman, director of Griffith University's Centre for Quantum Dynamics. He theorizes that countless parallel universes coexist with ours and that their reality can be scientifically tested.

Although many Americans find the geeks on TV’s Big Bang Theory charming and funny, there’s still a degree of stigma attached to being too passionate about science — and even more so about the wonky alternative culture of science fiction.

Trending

As I was telling my stepson Brian recently, in a big bookstore like Powell’s in Portland I’ll sometimes plot a course through the sci-fi section and then pause for a quick look at new offerings, as if momentarily diverted on my way toward something more respectable. Some part of me is still the little boy teased for raising his hand in class.

Despite a certain “cringe factor,” the fertile imaginations of sci-fi authors routinely leapfrog beyond what is considered possible in their own time. At age 10 or so, the local Carnegie library got me started on Jules Verne and H.G. Wells — both famous for sensing the future path of scientific progress. Our library also had a smattering of more-contemporary sci-fi offerings, including Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. But for Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Robert Heinlein and Clifford D. Simak, in the 1960s I’d have to thumb through the corner drug store’s paperback racks.

Some mid-20th century sci-fi authors’ ideas, prose and attitudes are clunky today, but there’s still plenty to appreciate.

Trending

Recently reading in a scientific abstract that “The idea of parallel universes in quantum mechanics has been around since 1957” brought to mind Simak’s 1940s stories in Astounding Science Fiction, gathered in one volume and published as City in 1952.

In October, a team from Griffith University and University of California proposed “that parallel universes really exist, and that they interact. That is, rather than evolving independently, nearby worlds influence one another by a subtle force of repulsion. They show that such an interaction could explain everything that is bizarre about quantum mechanics.”

While Einstein amusingly once observed that “You do not really understand something unless you can explain it to your grandmother,” the acclaimed American theoretical physicist Richard Feynman admitted, “I think I can safely say that nobody understands quantum mechanics.”

Explaining the concept of “Many-Interacting Worlds” in a press release from Griffith University, lead researcher Howard Wiseman said the idea is that “each universe branches into a bunch of new universes every time a quantum measurement is made. All possibilities are therefore realized — in some universes the dinosaur-killing asteroid missed Earth. In others, Australia was colonized by the Portuguese.”

This gets deep into the weeds very quickly. For example, what even constitutes a “measurement” is itself a prodigiously messy topic, at least to me.

But Wiseman’s work excites special interest because it appears to be testable — opening the possibility of learning that countless other universes nest together with ours and that their existence can be proven by observing the affects they have on subatomic particles.

In City, Simak imagines a world thousands of years in the future governed by dogs, the genetically jump-started descendants of our pets. “But for speech and hands, we might be dogs and dogs be men,” he observes. (As a dog man, this alone would make Simak a hero to me.)

Simak foresees that physically traveling across space to other stars is a failure for people, but we bequeath our curiosity to artificially self-aware robots who begin spreading across the galaxy in our place. Beyond this, he imagines a variety of outcomes for humanity — including transforming ourselves into another species adapted to life on Jupiter.

Perhaps genetic engineering will at least allow us to continue living on Earth after we’ve heated it back up to dinosaur-friendly conditions. However, of Simak’s scenarios for mankind, what most appeals to me is the possibility of being able to slip through some hidden seam in reality into an infinite complex of interconnected universes. In real life, interstellar travel is rendered very close to utterly impossible by the distances involved, but what if we could flip through innumerable versions of Earth, some of them empty and ready for settlement?

Simak calls these the cobbly worlds. Glimpses we sometimes sense about them are “Cobblies — the things behind the wall, the things that one hears and cannot identify — the dwellers in the next room.”

To me, there are inexplicable times when the boundaries of this world become indistinct — I’ll always remember walking through a remote mountain valley with my sister once late at night. Sober and mature, we both began feeling like children who hear faint whispers coming from an open grave. Nothing moved among the aspens and rocks, but reality was discernibly frail and wispy. Perhaps our noticing this popped a fresh new copy of the entire universe into existence. Or maybe it was all just nonsense we told ourselves.

Toward the end of his life, Simak spoke what seem to me to be extraordinarily wise words:

“I have asked at times what the purpose of life may be; I have tried to probe into the real meaning of intelligence, and I have at times wondered about the inevitability of death. … I have suggested that our intellectual capacity may be a tool designed … to bring about a complete understanding of the universe, if not by us humans, then by some other race of beings who evolve from us. … Any purpose achieved by any life is a triumph for all life and all life must be given credit.”

— M.S.W.

Matt Winters is editor and publisher of the Chinook Observer and Coast River Business Journal.

Perhaps genetic engineering will at least allow us to continue living on Earth after we’ve heated it back up to dinosaur-friendly conditions.