Turning toward each other rather than away is always the right choice

Published 8:00 pm Thursday, October 2, 2014

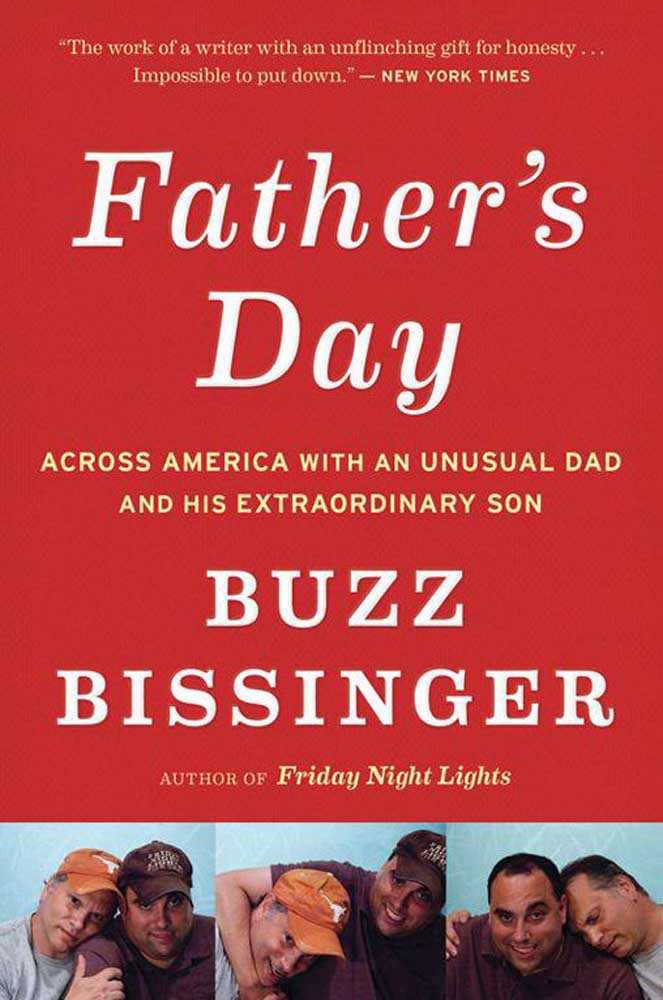

- “Father's Day” by the Long Beach Peninsula's Buzz Bissinger is a memoir about an epic road trip with a cherished son.

A considerably older kid with Down syndrome was my best friend for a time when I was 5. We had a gold-panning operation in the black sands of the slender north fork of the Popo Agie River, which trickled out of the Wind River Mountains, through my parents’ property and north past Arapahoe on its way to join the Yellowstone and Missouri. Black sand is a nearly worthless mix of iron-rich minerals. It has always been a clue placer miners look for. Black sands are the weeds in which gold hides. We were sure we were going to be Tootsie-Roll tycoons, skimming the thick gunk into empty jam jars for the smelter. With enthusiasm and a still-weak grasp of geology and basic math, I promised my buddy I’d split the profits — with him getting 100 percent. I was mortified to have to go back on the deal after Dad told me that split wouldn’t leave anything for me.

But he was a good-natured boy and comprehended percentages even less well than I.

Looking back, it was great being little, with no compulsion to feign superiority or spurn my friend because of a nasty social stigma.

There were more people than usual with Down syndrome and other intellectual disabilities in my hometown — and I’m not merely poking fun at cow-town politics. The State Training School was located there, which theoretically imparted career and life skills to mentally handicapped men, women and children. It worked for a few. One impressively industrious man was employed as a janitor in Jim Trimmer’s barbershop across from my dad’s law office.

For others, it was a forlorn and bestial prison, a place where your birth could be forgotten. As an adult, getting my hands on a secret internal audit was a mind-twisting glimpse into a place that I, like most of our neighbors, had always been content to drive by and ignore so long as its pretty lawns were well mowed.

In the convoluted way memory works, early childhood impressions of the Sun Dance came to mind last week while reading Father’s Day, a road-trip memoir by local author Buzz Bissinger. (Bissinger and his wife, former KMUN General Manager Lisa Smith, who has a story in this week’s Coast Weekend, are increasingly based on Washington’s Long Beach Peninsula.)

Zach and Gerry, Bissinger’s twin boys with his first wife, were prematurely born three minutes apart. Both were long hospitalized and each suffered chronic problems — painful issues that are glossed over in our joy about modern medicine being able to save the lives of seriously preterm infants.

Zach barely survived the ordeal and is a savant — someone who isn’t smart in the accepted sense, but has a remarkable memory for certain things. For one, he is able to perfectly recall maps — he’s sort a human global positioning satellite — a handy talent for a cross-country trip from Pennsylvania to Los Angeles. But in other ways, he is not a perfect traveling companion. Although displaying flashes of insight and wry humor, a brilliant conversationalist Zach is not.

Buzz is self-excoriating when it comes to his son, torturing himself for not being a better dad and more accepting of Zach’s condition.

The Sun Dance traditions taught at reservation school carved a deep wound in the imaginations of us little boys. An elaborate religious ceremony lasting days (see tinyurl.com/omjpy8n), it is unfairly known for the small part of it that once entailed men being pierced by “two small wooden skewers in the breast … which were fastened to the ends of a lariat,” which were tied to the center-pole of the dance grounds. Fasting, dancing, hanging, suffering could go on for many hours.

There are unintentional echoes of this in parts of Buzz’s book. All parents wish we were capable of being perfect stewards of our children’s future. In Buzz’s case, these regrets puddle around his feet like the blood beneath a sun dancer, all his admissions forming a kind of public sacrifice in the hope for a better future for his son — or at least a dignified old age after his guardians have died.

My mom, in some ways as progressive and compassionate a person as can be imagined, had something of an obsession when it came to families choosing to care for disabled children. In her view, they shouldn’t. Although I’d like to think she’d have thought differently if ever put to the test with her own kids, she adamantly thought institutionalization was better.

Buzz, at the end of his and Zach’s time on the road, arrived at a far more hopeful and humane conclusion. He learns to see in his son the reality of a human being doing his best to live a life with meaning. We’re left with the feeling that Zach’s dreams and future are just as valid as anyone’s.

I’m so glad Buzz keeps Zach close to heart and has helped formulate an independent adult life for him. Turning toward each other rather than away is always the right choice.

— MSW

Matt Winters is editor of the Chinook Observer and Coast River Business Journal.

The author learned to see in his disabled son a human being doing his best to live with meaning.