The dark side of religion – onstage Carlisle Floyd sets the biblical story of Susanna and the Elders in rural Tennessee

Published 2:52 am Friday, September 19, 2014

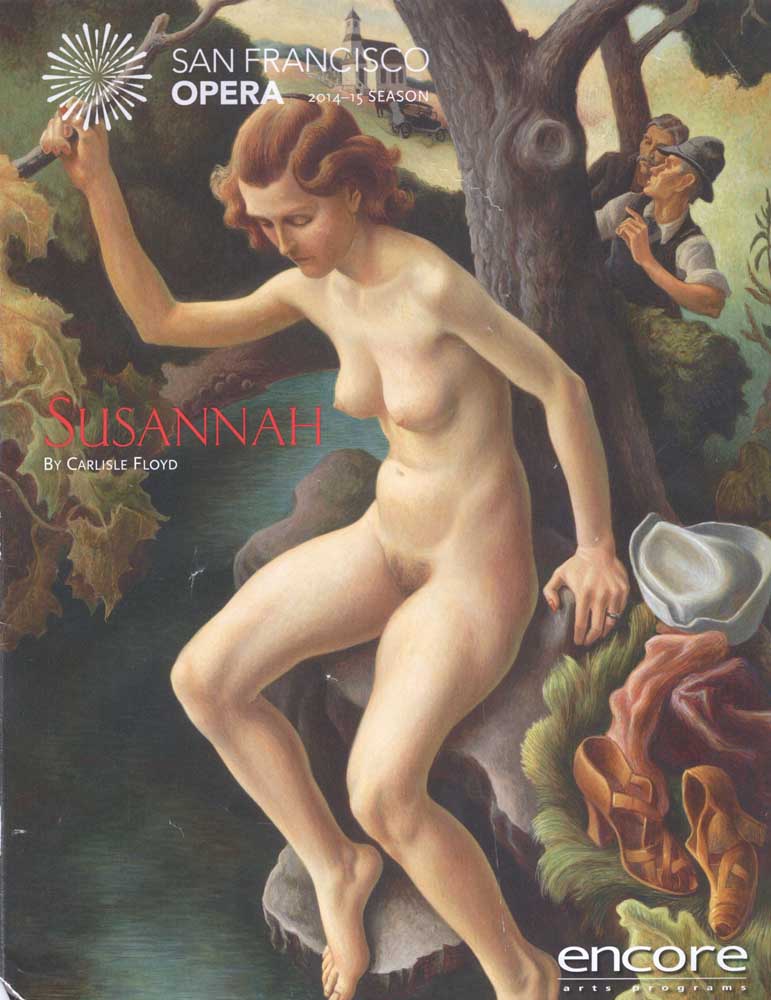

- The eminent Missouri artist Thomas Hart Benton depicted the biblical story of Susanna and the Elders in a 1938 painting. San Francisco Opera used the Benton painting on the program cover for its production of Carlisle Floyd's “Susannah.”

Susannah is the greatest piece of American music you’ve never heard of. It is tuneful, it conveys a moral message and packs a wallop.

The composer Carlisle Floyd transformed the biblical story of Susanna and Elders into an opera set in rural Tennessee. Like its source in the Apocrypha, the opera is about the dark side of religion. Appearing in 1955, the opera was a retort to McCarthyism, which then dominated American politics and made cowards of some big strong men in Congress.

To an American listener who is fatigued with atonal classical music of the 20th century, Floyd’s melodies are beguiling. Susannah is part of San Francisco Opera’s fall season.

The hero in the root story — in the Apocrypha of the Bible — is Daniel, who punishes church elders who lie about Susanna after blackmailing her for sex.

There is no hero in Floyd’s retelling. After the elders of a Tennessee church see young Susannah bathing in a creek that’s used for baptisms, they isolate her within their congregation, which is already prepared to shun her. In the opera’s first scene, a church woman watches Susannah square dancing and sings: “She is a shameless girl, she is. Throwin’ herself at men.”

The opera’s pivotal character, The Rev. Olin Blitch, is a morally compromised man who pursues Susannah and, in front of the congregation, invites her to confess her sins.

Unlike the biblical root story, Floyd’s opera ends badly for everyone. Susannah, who opens the opera as a sunny personality, leaves it jaded. Attempting to atone for his own error, Rev. Blitch says: “The woman sitting in the rear has been a victim of our error. She is innocent.”

When Blitch asks Susannah’s forgiveness, she replies: “Forgive? I’ve forgot what that word means.”

When he describes the gestation of this opera’s church elements, Floyd says the revival meetings he saw as a boy in South Carolina were frightening. When the American singer Norman Treigle played Blitch in the first big stage production, he made the revival scene into an awesome moment.

One character offers a dose of mercy. It is Susannah’s brother, Sam. He describes the vengeance of the church congregation: “They take it out on you. It must make the good Lord sad.”

Floyd makes a connection between the church congregation depicted in the opera and the political demagoguery and oppressiveness of the 1950s. He says: “It’s mass coercion to conform, whether people are really convinced of the doctrine or not. You simply bend the knee without question, which is the basis of any totalitarian society.”

If you want to experience Susannah’s power, the live performance recording made in the New Orleans performance in 1962 is your ticket. Treigle’s performance is inspired. Floyd’s father, a Methodist minister, was present at the work’s premiere at Florida State University. He subsequently admitted to his son that he considered walking out during the revival scene.

The opera’s rise was meteoric. It quickly was produced by the New York City Opera. It has become the most performed American opera, with more than 800 performances, here and abroad. It was chosen for performance at the Brussels World’s Fair of 1958.

Floyd has also put John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men on the operatic stage, as well as 10 other works.

— S.A.F.

Susannah is the greatest piece of American music you’ve never heard of.